| |

|

|

. Men never do evil so completely and

cheerfully

as when they do it from religious conviction.

|

|

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), Pensées

|

The

concept of a just or holy war is an ancient

one. The Jews used the concept, and it was probably from them

that Christians and Muslims adopted it. All three principal

monotheistic religions still accept the idea and continue to

use it. For Jews it is a kherem , for Muslims it is

a jihad, and for Christians a crusade. The

concept of a just or holy war is an ancient

one. The Jews used the concept, and it was probably from them

that Christians and Muslims adopted it. All three principal

monotheistic religions still accept the idea and continue to

use it. For Jews it is a kherem , for Muslims it is

a jihad, and for Christians a crusade.

The concept of a crusade was developed in the eleventh century

as a result of organised Christian forces fighting Muslims in

Sicily and Spain. The best known crusades were a series of military

expeditions promoted by the papacy during the Middle Ages, aimed

at taking the Holy Land for Christendom. The Holy Land had been

in the hands of the Muslims since 638, and it was against them

that the crusades were, at least nominally, directed. Desire

for adventure, conquest and plunder seems to have been at least

as influential in attracting Christians to the cause as any

desire to restore Christ's supposed patrimony.

The

Church regarded crusaders as military pilgrims. They took vows

and were rewarded with privileges of protection for their property

at home. Any legal proceedings against them were suspended.

Another major inducement was the offer of indulgences for the

remission of sin. Knights were especially attracted by what

were effectively Get-Out-Of-Hell-Free cards allowing them to

commit any sins throughout the rest of their lives without incurring

liability in this or the next world. During the Crusades the

Western Church developed new types of holy warrior. These were

military monks such as the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar.

They were literally both soldiers and monks, and took vows for

both callings, fulfilling their holy duties by killing God's

enemies. Originally they followed the rule of St Benedict. The

Church regarded crusaders as military pilgrims. They took vows

and were rewarded with privileges of protection for their property

at home. Any legal proceedings against them were suspended.

Another major inducement was the offer of indulgences for the

remission of sin. Knights were especially attracted by what

were effectively Get-Out-Of-Hell-Free cards allowing them to

commit any sins throughout the rest of their lives without incurring

liability in this or the next world. During the Crusades the

Western Church developed new types of holy warrior. These were

military monks such as the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar.

They were literally both soldiers and monks, and took vows for

both callings, fulfilling their holy duties by killing God's

enemies. Originally they followed the rule of St Benedict.

Nine crusades are generally recognised, although there were

many others. Many of them collapsed before they got out of Christendom.

Some, such as the Children's Crusade, are now disowned as crusades.

Others were directed not against Muslims but fellow Christians

in Europe, the Church at Constantinople, Christian emperors

and kings, sects who rejected the Roman Church, even powerful

Italian families hostile to the pope of the day.

The First Crusade The First Crusade was planned

by Pope Urban II and more than 200 bishops at the Council of

Clermont. It was preached by Urban between 1095 and 1099. He

assured his listeners that God himself wanted them to encourage

men of all ranks, rich and poor, to go and exterminate Muslims.

He said that Christ commanded it. Even robbers, he said, should

now become soldiers of Christ*.

Assured that God wanted them to participate in a holy war, masses

pressed forward to take the crusaders' oath. They looked forward

to a guaranteed place in Heaven for themselves and to an assured

victory for their divinely endorsed army. In 1095, at the Council

of Clermont, at the very start of the First Crusade, Urban declared

that a war could be not only a bellum iustum (just war),

but could, in certain cases, be a bellum sacrum (holy

war). The pope did not appoint a secular military supreme commander,

only a spiritual one, the Bishop of Le Puy. Initial expeditions

were led by two churchmen, Peter the Hermit and Walter the Penniless.

Peter was a monk from Amiens, whose credentials were a letter

written by God and delivered to him by Jesus. He assured his

followers that death in the Crusades provided an automatic passport

to Heaven.

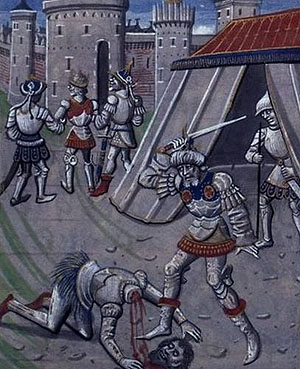

|

Peter the Hermit leading the advance

party of the First Crusade

|

|

|

One German contingent in the Rhine valley was granted a further

sign from God. He sent them an enchanted goose to follow. It

led them to Jewish neighbourhoods of Spier, where they took

the divine hint and massacred the inhabitants. Similar massacres

followed at Worms, Mainz, Metz, Prague, Ratisbon and other cities.

These pogroms completed, Peter the Hermit's army marched through

Hungary towards Turkey. On the way they killed 4,000 Christians

in Zemun (present day Semlin), pillaged Belgrade, and set fire

to the towns around Niš. They thieved and murdered all

the way to Constantinople, by which time only about a third

of the initial force remained. The Emperor was astonished. He

had asked for trained mercenaries, but what arrived was a murderous

rabble. To minimise the risks of danger to his own city he allowed

the crusaders to proceed without entering the city. Once across

the Bosphorus, they continued as before. Marching beyond Nicæa,

a French contingent ravaged the countryside. They looted property,

and robbed, tortured, raped and murdered the mainly Christian

inhabitants of the country, reportedly roasting babies on spits*.

Some 6,000 German crusaders, including bishops and priests,

jealous of the French success, tried to emulate it. However,

this time an army of Turks arrived and chopped the holy crusaders

to pieces. Survivors were given the chance to save their lives

by converting to Islam, which some did, including their leader

Rainauld, setting a precedent for many future crusaders*.

The principal expedition that followed was more organised,

although crusaders continued to threaten their Christian allies

in Constantinople on the way. The Christian Emperor was shocked

to find his capital under attack by Western Christians in Holy

Week*. He developed a technique

for bringing the barbarian Westerners under control by speedily

processing batches of them as they arrived. His technique was

to induce them to swear fealty to him, then swiftly move them

across the Bosphorus before the next batch arrived. On the far

side of the water their massed forces were no threat to the

city. Apart from further devastating the countryside they could

do little but prepare for their first encounter with their non-Christian

enemies.

Sieges

were laid to a series of Muslim cities. Crusaders had little

respect for their enemies and enjoyed catapulting the severed

heads of fallen Moslem warriers into besieged cities. After

a victory near Antioch, crusaders brought severed heads back

to the besieged city. Hundreds of these heads were shot into

the city, and hundreds more impaled on stakes in front of the

city walls. A crusader bishop called it a joyful spectacle for

the people of God. When Muslims crept out of the city at night

to bury their dead the Christians left them alone. Then in the

morning the Christians returned, and dug up the corpses to steal

gold and silver ornaments*. Sieges

were laid to a series of Muslim cities. Crusaders had little

respect for their enemies and enjoyed catapulting the severed

heads of fallen Moslem warriers into besieged cities. After

a victory near Antioch, crusaders brought severed heads back

to the besieged city. Hundreds of these heads were shot into

the city, and hundreds more impaled on stakes in front of the

city walls. A crusader bishop called it a joyful spectacle for

the people of God. When Muslims crept out of the city at night

to bury their dead the Christians left them alone. Then in the

morning the Christians returned, and dug up the corpses to steal

gold and silver ornaments*.

When the crusaders took Antioch in 1098 they slaughtered the

inhabitants. Later the Christians were in turn besieged by Muslim

reinforcements. The crusaders broke out, putting the Muslim

army to flight and capturing their women. The chronicler Fulcher

of Chartres was proud to record that on this occasion nothing

evil (i.e. sexual) had happened, although the women had been

murdered in their tents, pierced through the belly by lances.

Time and time again Muslims who surrendered were killed or sold

into slavery. This treatment was applied to combatants and citizens

alike: women, children, the old, the infirm — anyone and

everyone. At Albara the population was totally extirpated, the

town then being resettled with Christians, and the mosque converted

into a church. Often, the Christians offered to spare those

who capitulated, but it was an unwise Muslim who accepted such

a promise. A popular technique was to promise protection to

all who took refuge in a particular building within the besieged

city. Then after the battle, the Christians had an easy time:

the men could be massacred and the women and children sold into

slavery without having to carry out searches. Clerics justified

this by claiming that Christians were not bound by promises

made to infidels, even if sworn in the name of God. At Maarat

an-Numan the pattern was repeated. The slaughter continued for

three days, both Christian and Muslim accounts agreeing on the

main points, although each has its own details. The Christian

account describes how the Muslims' bodies were dismembered.

Some were cut open to find hidden treasure, while others were

cut up to eat*. The Muslim

account mentions that over 100,000 were killed.

When the crusaders captured Jerusalem on the 14 th July 1099,

they massacred the inhabitants, Jews and Muslims alike, men,

women and children. The killing continued all night and into

the next day. Jews who took refuge in their synagogue were burned

alive. Muslims sought refuge in the al-Aqsa mosque under the

protection of a Christian banner. In the morning crusaders forced

an entry and massacred them all, 70,000 according to an Arab

historian, including a large number of scholars. As one churchman

explained

But now that our men had possession of the walls and towers,

wonderful sights were to be seen. Some of our men (and this

was more merciful) cut off the heads of their enemies; others

shot them with arrows, so that they fell from the towers;

others tortured them longer by casting them into the flames.

Piles of heads, hands, and feet were to be seen in the streets

of the city. It was necessary to pick one's way over the bodies

of men and horses. But these were small matters compared to

what happened at the Temple of Solomon, a place where religious

services are ordinarily chanted. What happened there? If I

tell the truth, it will exceed your powers of belief. So let

it suffice to say this much, at least, that in the Temple

and porch of Solomon, men rode in blood up to their knees

and bridle reins. Indeed, it was a just and splendid judgment

of God that this place should be filled with the blood of

the unbelievers, since it had suffered so long from their

blasphemies. The city was filled with corpses and blood*.

Even before the killing was over the crusaders went to the

Church of the Holy Sepulchre "rejoicing and weeping for

joy" to thank God for his assistance.

Neither was this an isolated incident. It was wholly typical.

When the crusaders took Caesarea in 1101, many citizens fled

to the Great Mosque and begged the Christians for mercy. At

the end of the butchery the floor was a lake of blood. In the

whole city only a few girls and infants survived. Soon afterwards,

there was a similar massacre at Beirut. Such barbarity shocked

the Eastern world and left an impression of the Christian West

that has still not been forgotten in the third millennium.

By 1101 reinforcements were on the way, under the command of

the Archbishop of Milan, to support the Frankish crusaders already

in the Holy Land. Mainly Lombards, the new troops lived up to

the record of their French and German predecessors, robbing

and killing Christians on the way, and blaming the Byzantine

Emperor for the consequences of their own shortcomings. At the

first engagement with the enemy they fled in panic leaving their

women and children behind to be killed or sold in slave markets.

As Sir Steven Runciman, a leading historian of the period says:

the Byzantines were "shocked and angered by the stupidity,

the ingratitude and the dishonesty of the crusaders"*.

They also questioned the crusaders" loyalty to their Byzantine

allies. The crusaders had purportedly gone to help Byzantium,

and had sworn to restore to the Emperor any of his territory

that they recaptured, but not a single one ever did so.

Indeed, Eastern Christians were regarded as enemies as much

as the Muslims.

Fired by the success of the crusade against the Muslims, Pope

Paschal II (the successor to Urban II) gave his blessing in

1105 to a holy war against his fellow Christians in the East.

Preached by a papal legate, the new crusade sought to subjugate

the Eastern Empire to Rome. This was unprecedented treachery

and undisguised imperialism. For the time being such perfidy

got the crusaders nowhere.

The Second Crusade Pope Eugene III proclaimed

The Second Crusade in 1145. It was preached by St Bernard, a

leading Cistercian theologian who declared that "The Christian

glories in the death of a pagan, because thereby Christ himself

is glorified". He also pointed out that anyone who kills

an unbeliever does not commit homicide but malicide*;

in other words they kill not a man but an evil. In his Praise

Of The New Knighthood, wtitten before the second Crusade,

he wrote: "'The knight of Christ may strike with confidence

and die yet more confidently; for he serves Christ when he strikes,

and saves himself when he falls.... When he inflicts death,

it is to Christ's profit, and when he suffers death, it is his

own gain." He knew how to sell a crusade to believers.

His spiel was reminiscent of that of a high-pressure salesman

selling to credulous punters:

But to those of you who are merchants, men quick to seek

a bargain, let me point out the advantages of this great opportunity.

Do not miss them. Take up the sign of the cross and you will

find indulgence for all sins that you humbly confess. The

cost is small, the reward is great.... *

The Second Crusade was led by the greatest potentates in western

Europe: King Louis VII of France and the German Emperor Conrad

III. Once again churchmen promoted anti-Semitism in Germany

and France. Without the aid of a single enchanted goose the

crusaders once again found unbelievers in their midst. Inspired

by a Cistercian monk, they massacred Jews throughout the Rhineland

— notably in Cologne, Mainz, Worms, Spier and Strasbourg.

The initial object of the Second Crusade was to recapture Edessa

(in what is now eastern Turkey), which had fallen to the Muslims

in 1144. Initial contingents were led by military commanders

like the bishops of Metz and Toul. On the way, travelling by

sea, the crusaders besieged Lisbon, which at that time was a

Muslim city. After four months the garrison surrendered, having

been promised their lives and their property if they capitulated.

They did capitulate and were then massacred. Only about a fifth

of the original crusader force got as far as Syria, where the

real crusade started. It proved a failure, at least partially

because tactical targets were selected for religious rather

than military reasons. A military tactician might have gone

for Aleppo, but the crusade leaders agreed on mounting an attack

on Damascus, apparently because they recognised its name as

biblical. The leaders argued amongst themselves until the crusade

collapsed in 1149, having failed to take either Edessa or Damascus.

The whole thing had been a disaster. As Runciman put it:

…when it reached its ignominious end in the weary

retreat from Damascus, all that it had achieved had been to

embitter relations between the Western Christians and the

Byzantines almost to breaking-point, to sow suspicions between

the newly-come Crusaders and the Franks resident in the East,

to separate the western Frankish princes from each other,

to draw the Muslims closer together, and to do deadly damage

to the reputation of the Franks for military prowess*.

The Muslim Turks extended their rule to Egypt soon afterwards.

St Bernard had been promised a victory by God, but instead of

this he had provided a complete disaster. Bernard and his supporters

tried hard to work out why God's purpose had been so badly frustrated.

Perhaps the best solution was that the outcome had been a great

success after all, because it had transferred so many Christian

warriors from God's earthly army to his heavenly one. Not everyone

was convinced. Meanwhile the Christian forces resident in the

East accommodated themselves to the realities of Eastern life.

Eventually they would come to terms with the fact that until

their arrival Muslims, Jews and Christians had lived together

in amity. Resident Christians often preferred their old Muslim

masters to their new Christian ones.

Muslim captives who chose to convert to Christianity rather

than die were allowed to, but only if there were no further

monetary complications. When Cairo offered 60,000 dinars to

the Templars for the return of a putative convert, his Christian

instruction was promptly suspended and he was sent in chains

to Cairo to be mutilated and hanged. Such incidents brought

little glory to either side, but it is fair to say that Muslim

princes generally conducted themselves with a degree of honour

and chivalry lacking amongst the Christians.

Jerusalem Retaken In 1187,

almost 90 years after it had been captured by the Christian

army of the First Crusade, Jerusalem was retaken by the Muslim

warrior Saladin (c.1137-1193). Originating from Tikrit in modern-day

Iraq, Saladin had first demonstrated his military prowess in

the 1160s in campaigns against crusaders in Palestine. Succeeding

his uncle as a vizier in Egypt, he conquered Egypt in 1175 and

then set about improving that country's economy and military

strength. Following further campaigns in Syria and Mesopotamia,

in 1186 he proclaimed a jihad that led to his capturing

Jerusalem for the Muslims in the following year.

In

addition to his abilities as a military leader, Saladin is renowned

for his chivalry and merciful nature. It is known, for example,

that in his struggles against the crusaders, he provided medical

assistance on the battlefield to the wounded of both sides,

and even allowed Christian physicians to visit Christian prisoners.

Once the battle to retake Jerusalem was over, no one was killed

or injured, and not a building was looted. The captives were

permitted to ransom themselves, and those who could afford to

do so ransomed their vassals as well. Many thousands could not

afford their ransom and were held to be sold as slaves. The

military monks, who could have used their vast wealth to save

their fellow Christians from slavery, declined to do so. The

head of the Church, the patriarch Heraclius, and his clerics

looked after themselves. The Muslims saw Heraclius pay his ten

dinars for his own ransom and leave the city bowed with the

weight of the gold that he was carrying, followed by carts laden

with other valuables. As the prisoners who had not been ransomed

were led off to a life of slavery, Saladin's brother Malik al-Adil

took pity. He asked his brother for 1,000 of them as a reward

for his services, and when he was granted them he immediately

gave them their liberty. This triggered further generosity amongst

the victorious commanders, culminating in Saladin offering gifts

from his own treasury to the Christian widows and orphans. As

a contemporary historian has remarked, "His mercy and kindness

were in strange contrast to the deeds of the Christian conquerors

of the First Crusade"*. In

addition to his abilities as a military leader, Saladin is renowned

for his chivalry and merciful nature. It is known, for example,

that in his struggles against the crusaders, he provided medical

assistance on the battlefield to the wounded of both sides,

and even allowed Christian physicians to visit Christian prisoners.

Once the battle to retake Jerusalem was over, no one was killed

or injured, and not a building was looted. The captives were

permitted to ransom themselves, and those who could afford to

do so ransomed their vassals as well. Many thousands could not

afford their ransom and were held to be sold as slaves. The

military monks, who could have used their vast wealth to save

their fellow Christians from slavery, declined to do so. The

head of the Church, the patriarch Heraclius, and his clerics

looked after themselves. The Muslims saw Heraclius pay his ten

dinars for his own ransom and leave the city bowed with the

weight of the gold that he was carrying, followed by carts laden

with other valuables. As the prisoners who had not been ransomed

were led off to a life of slavery, Saladin's brother Malik al-Adil

took pity. He asked his brother for 1,000 of them as a reward

for his services, and when he was granted them he immediately

gave them their liberty. This triggered further generosity amongst

the victorious commanders, culminating in Saladin offering gifts

from his own treasury to the Christian widows and orphans. As

a contemporary historian has remarked, "His mercy and kindness

were in strange contrast to the deeds of the Christian conquerors

of the First Crusade"*.

In contrast to the generally honourable behaviour of the Muslims,

the Christians repeatedly made promises under oath and them

reneged upon them, often with the encouragement of the priesthood.

In 1188 the King of Jerusalem, Guy, who had been captured by

Saladin, was released. Guy had solemnly sworn that he would

leave the country and never again take arms against the Muslims.

Immediately, a cleric was found to release him from his oath.

Despite this sort of behaviour, Muslim leaders generally stuck

to their own promises. They were rather bemused by the cynical

behaviour of the Western Christians. Often the cynicism worked

to the Muslims" advantage. For example, Saladin was pleasantly

surprised to find that Italian city states were prepared to

sell him high quality weapons to be used against crusaders.

When the Emperor in Constantinople heard of the Muslim victory,

he sent an embassy to congratulate its leaders. Eastern Christians

had already generally allied themselves with the Muslims, regarding

them as fairer and more civilised rulers than the followers

of the Church of Rome. Now they asked to stay in Jerusalem,

were allowed to do so, and gave "prodigious service"

to their new masters.

The

Third Crusade After the loss of Jerusalem, a Third

Crusade was preached by Pope Gregory VIII. It was jointly led

by Frederick Barbarossa, Philip of France, and Richard I of

England (The Lionheart). The Archbishop of Canterbury, Baldwin,

went along too. Richard had been crowned on 3 rd September in

1189 with crusading fervour already in the air. English Christians

emulated their continental co-religionists, and took to murdering

Jews, starting with those who had come to offer presents to

their new king. This sparked further persecutions throughout

the country, most notably in York. Soon the crusaders, including

those who had engaged in the murder of Jews, departed for the

East along with their continental co-religionists. Frederick

Barbarossa died on the way, an event that mystified the crusaders,

but which Muslims immediately recognised as a miracle wrought

by God for the one true faith. Philip and Richard squabbled

and attempted to bribe each other's armies to change allegiance

(three gold pieces per month for English knights who joined

Philip: four for French knights who joined Richard). The

Third Crusade After the loss of Jerusalem, a Third

Crusade was preached by Pope Gregory VIII. It was jointly led

by Frederick Barbarossa, Philip of France, and Richard I of

England (The Lionheart). The Archbishop of Canterbury, Baldwin,

went along too. Richard had been crowned on 3 rd September in

1189 with crusading fervour already in the air. English Christians

emulated their continental co-religionists, and took to murdering

Jews, starting with those who had come to offer presents to

their new king. This sparked further persecutions throughout

the country, most notably in York. Soon the crusaders, including

those who had engaged in the murder of Jews, departed for the

East along with their continental co-religionists. Frederick

Barbarossa died on the way, an event that mystified the crusaders,

but which Muslims immediately recognised as a miracle wrought

by God for the one true faith. Philip and Richard squabbled

and attempted to bribe each other's armies to change allegiance

(three gold pieces per month for English knights who joined

Philip: four for French knights who joined Richard).

Eventually, Philip gave up and went home. Richard went on to

capture Acre in 1191. Saladin was unable to pay for the release

of the survivors quickly enough, so Richard ordered the massacre

of his 2,700 captives, many of them women and children. They

waited in line, each watching the one in front have their throat

slit. Wives were slaughtered at the side of their husbands,

children at the side of their parents while bishops blessed

the proceedings. Corpses were then cut open in the hope of finding

swallowed jewels.

Richard found further success difficult to come by, and a truce

was made with Saladin, although Richard felt free to break it

when it suited him. Despite Richard's behaviour, Saladin continued

to treat him with respect when they met on the battlefield,

apparently because Richard's fighting prowess impressed him.

When Richard's horse fell, wounded in battle outside Jaffa in

August 1192, Saladin sent a groom through the mêlée

with fresh mounts for him. The Lionheart's treatment by his

Muslim enemy contrasted with his treatment by his own Christian

allies. On his way home later that year Richard was captured

and imprisoned by a fellow crusader, Leopold, Duke of Austria.

He was eventually released on payment of the Christian sum of

150,000 marks (£100,000), literally a king's ransom.

The Fourth Crusade The Fourth Crusade was

preached by Pope Innocent III and lasted from 1202 to 1204.

Although intended to regain the Holy Land from the Muslims by

way of Egypt, the crusade was hijacked by the Venetians and

directed against the Christian cities of Zara and then Constantinople,

which offered a softer target and richer pickings. Constantinople

was taken, the Emperor deposed, and Baldwin of Flanders was

set up in his place. The victorious crusaders amused themselves

in the usual way, even though this was the capital of Christendom.

As well as the standard bout of destruction, the men of the

cross desecrated imperial tombs, plundered churches, stole holy

relics, wrecked houses, vandalised libraries, destroyed whatever

loot they could not carry, raped nuns, and murdered at will.

They also set a prostitute on the patriarch's throne in Sancta

Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom, the greatest Church in

Christendom. Later a Latin (i.e. Roman Catholic) patriarch was

installed, and the Venetians shipped off the remaining treasures

to their own city, where some of them remain to this day. We

have sympathetic accounts of these events, including one of

an Abbot threatening to kill an Orthodox priest if he did not

hand over a stash of “powerful” relics*.

The Eastern Churches still harbour bitter resentment about the

behaviour of Western Christians during this time. Here is a

modern Orthodox bishop on the subject:

Eastern Christendom has never forgotten those three appalling

days of pillage. "Even the Saracens are merciful and

kind," protested Nicetas Choniates [a contemporary historian],

"compared with these men who bear the Cross of Christ

on their shoulders". What shocked the Greeks more than

anything was the wanton and systematic sacrilege of the Crusaders.

How could men who had specially dedicated themselves to God's

service treat the things of God in such a way? As the Byzantines

watched the Crusaders tear to pieces the altar and icon screen

in the Church of the Holy Wisdom, and set prostitutes on the

Patriarch's throne, they must have felt that those who did

such things were not Christians in the same sense as themselves*.

The Western Church saw nothing wrong with its conduct. It is

true that the Pope was initially irritated by the crusade having

been diverted to attack Zara. But His Holiness was soon reconciled

by a victory in his name over the Emperor, and any pretence

that the crusade was ever intended to fight the infidel was

abandoned. A papal legate, Peter of Saint-Marcel, issued a decree

absolving the crusaders from having to proceed further to fight

the Muslims. The new Emperor in Constantinople, Baldwin, wrote

to the Pope about the sack of the city as "a miracle that

God had wrought". The Pope rejoiced in the Lord and gave

his approval without reserve*.

Modern historians tend to take a different view. As Sir Steven

Runciman put it "There was never a greater crime against

humanity than the Fourth Crusade"*.

The Cathar wars or Albigensian Crusade

In 1208 Pope Innocent III launched crusades against the Cathars

in southern France, and in 1211 against Muslims in Spain, but

it was difficult to raise interest in expeditions to the more

distant and dangerous Holy Land.

More on the persecution

of the Cathars >

The Children's Crusade

The year 1212 saw the so-called Children's Crusade. This crusade

was preached by a French shepherd boy aged around 12, inspired

by a vision of Christ. Christ gave him a letter for the King

of France, and despite the King's indifference, the boy succeeded

in rousing 30,000 recruits, none over the age of 12. The crusader

children were blessed by priests and marched off to Marseilles.

The idea was that God would protect them and supply them with

suitable fighting skills. He would even part the sea so that

they could walk from Marseilles to the Holy Land. But God declined

to perform his promised miracle at Marseilles. Instead two men,

monks according to one tradition, Hugh the Iron and William

the Pig according to another, offered the children ships free

of charge to take them to their destination. Most accepted,

embarked, and were promptly sold as slaves to African Muslims.

This was not an isolated incident. Roman Catholic traders were

engaged in an established commerce involving the sale of young

boys to Muslim rulers*.

Some 40,000 German children also set out on the crusade, but

God declined to perform his promised miracle for them either.

How many ever arrived to fight, if any at all, is not known.

Few ever returned home.

Meanwhile in the Holy Land the resident Christians were becoming

ever more accustomed to Eastern life. They wore robes and turbans,

ate Eastern food, married Eastern women and learned Eastern

medicine. Alliances were made between powerful rulers, often

irrespective of religion. Christians accepted Muslims as their

feudal Lords and Muslims accepted Christians as theirs.

The Fifth Crusade This crusade was preached

by Pope Innocent III but undertaken in the reign of Pope Honorius

III. It was led by Cardinal Pelagius of Lucia and lasted from

1217 to 1221. Although ultimately intended to recover Jerusalem,

the main force was initially directed against Egypt. Damietta

(a Mediterranean port on the Nile delta) was besieged. Saladin

proposed a deal. He would cede Jerusalem, all central Palestine,

and Galilee if the crusaders would spare Damietta. Pelagius

rejected this offer, against military advice.

Damietta duly fell to the Christians. The surviving inhabitants

were sold into slavery, and their children handed over to the

Christian priests to be baptised and trained into the service

of the Church. But Saladin soon recovered Damietta by force.

The Christian campaign had been another failure, undermined

by a combination of personal and national jealousies along with

the lack of strategic insight on the part of Cardinal Pelagius,

a man who has been described as "an ignorant and obstinate

fanatic". As the defeated Christians sailed off, stories

of their atrocities triggered a wave of persecution of Christians

communities in Egypt, which until then had happily coexisted

with their Muslim masters for centuries.

The Sixth Crusade The Sixth Crusade was proposed

by Pope Gregory IX, but found few takers, previous crusades

having proved such failures. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick

II organised his own crusade while under sentence of excommunication,

and pursued it between 1222 and 1229. Despite the Pope's machinations

and much to his embarrassment Frederick's military and strategic

skill led to a negotiated settlement under which Nazareth, Bethlehem,

and Jerusalem came under Christian control. On his return to

Europe the victorious Frederick crushed the papal forces that

had been sent to destroy him, and the Pope had no choice but

to lift the sentence of excommunication.

The Seventh Crusade The Seventh Crusade lasted

from 1248 to 1254. It was initiated under Pope Innocent IV,

Jerusalem having been lost to the Muslims again in 1244. It

was led by King Louis IX of France ( St Louis) who started by

attacking Egypt. Once again Damietta was captured, and once

again the Sultan offered to exchange it for Jerusalem. Once

again the offer was rejected, and once again the Muslims won

Damietta back by force of arms. Louis himself was captured and

had to be ransomed for 400,000 bezants (gold coins). After his

release he went to the Holy Land but failed to recover the holy

cities, and so gave up and went home.

Innocent's successor, Pope Alexander IV, tried to organise

yet another crusade, this time against the Mongols, but he was

unsuccessful. Had he had a better grasp of strategy he might

instead have allied Western Christendom with the Asian powers.

Nestorian Christianity was still influential in Asia, and the

Mongols might easily have become allies, some of their leaders

having already been baptised. Western and Eastern forces combined

could have overcome the forces of Islam. In 1254 the Great Khan

Mongka, whose mother had been a Nestorian Christian, had offered

to recover Jerusalem for the Christians, if they would co-operate.

But European Christians were unwilling to co-operate with each

other, much less a remote and unknown semi-heathen whose mother

had been a heretic. In time the victorious Mongols would themselves

convert to Islam and spread their new religion throughout Asia,

eclipsing Christianity from the Levant to the Far East.

The Eighth Crusade The Eighth Crusade was

proposed by Pope Gregory X, but not organised until a later

reign. It lasted only from 1270 to 1271, and was initially led

once again by St Louis. An English contingent was made up largely

of men who needed to hold on to lands they had taken by force

in the baronial wars of the 1260s. By joining a crusade they

were assured of the protection of the Church, and thus able

to keep their newly acquired property. The project was another

failure. It collapsed after Louis died of disease while attacking

Carthage (modern Tunis).

The Ninth Crusade The Ninth Crusade continued

St Louis's Eighth Crusade. It was led by Prince Edward, the

future English King Edward I, between 1271 and 1272. Edward

reached the Holy Land and was mystified by what he found. The

Venetians were supplying the Sultan with all the timber and

metal he needed to manufacture his armaments, while the Genoese

controlled the Egyptian slave trade. Like Edward, new arrivals

were generally surprised by the realities of life in the East.

Italian city states jostled with each other for trade with Christians

and Muslims without distinction. Senior churchmen paralysed

strategic military initiatives. Noble families argued and betrayed

each other without compunction. So did the representatives of

European nation states, jealous of each other's favour or success.

Members of the Eastern and Western Churches bickered continuously.

Military Orders squabbled with each other and subverted military

expeditions when they threatened their own commercial interests.

The Knights Templar created the first true multinational banking

corporation serving Christians and Muslims alike, while Muslim

Assassins continued to pay homage to the Hospitallers. Native

Christians resented their supposed saviours from the West, and

would have preferred life under Byzantine or Muslim rulers.

Edward got nowhere in such a milieu, so alien to his preconceptions.

Like earlier crusades, this one fizzled out, a total failure.

Civil wars in the remaining Christian territories in the East

hastened the end of the crusading period in the Holy Land. Christian

princes burned each other's castles and besieged each other

in their strongholds. Western Christians were regarded as barbarians

by almost everyone. They were likely to kill anyone on a whim,

whether Muslim, Jew or Christian. In 1290 newly arrived Italian

crusaders went on a Muslim-killing spree in Acre, but since

they assumed that any man with a beard was a Muslim, they murdered

many Christians as well. The Italians seem to have been even

worse than most of their fellow crusaders:

…the Italians, with their arrogance, their rivalries

and the cynicism of their policy, caused irremediable harm.

They would hold aloof from vital campaigns and openly parade

the disunity of Christendom. They supplied the Muslims with

essential war-material. They would riot and fight each other

in the streets of the cities*.

Further Crusades In 1297 Pope Boniface VIII

preached a crusade against the Colonnas, a powerful Italian

family that regarded the papacy almost as its hereditary possession,

and that felt free to take papal treasure at will, even when

the papacy was temporarily out of its control. The crusade was

announced, complete with indulgences, but Colonna forces captured

the Pope. Although he was rescued, he died a month later, a

broken man. New crusades against the Turks were proposed by

a number of fourteenth century popes, but they never got started.

Benedict XII , Innocent VI , Urban V and Gregory XI all proposed

them, and Urban even got as far as proclaiming his in 1363,

but nothing ever came of it.

King Peter I of Cyprus organised his own crusade, which attacked

and took Alexandria in 1365. The subsequent massacres followed

traditional lines of Jerusalem in 1099 and Constantinople in

1204. Crusaders massacred native Christians indiscriminately

along with Jews and Muslims. Some 5,000 survivors, representing

all three religions, were sold into slavery. European triumphalism

over this victory soon waned. Muslim bitterness was revived,

Venetian merchants were almost ruined, the spice and silk trades

dried up, pilgrims" access to the Holy Land was imperilled,

and native Eastern Christians were persecuted once more. Christendom

became alarmed at what might happen next. Providentially, Peter

was assassinated in 1369, and a peace treaty was signed the

following year.

In the fifteenth century, Pope Martin V organised an unsuccessful

crusade against the Hussites, a Christian sect in Bohemia. Pope

Eugene IV tried to organise another crusade to recover the Holy

Land, but it was a failure. A few years later Cardinal Cesarini

persuaded the King of Hungary to support another crusade against

the Turks. A ten-year truce was in place, but the Cardinal gave

assurances that an oath sworn to a Muslim was invalid. Battle

was joined at Varni in Bulgaria, in 1444, where the Christian

forces were roundly defeated, leaving Cardinal Cesarini amongst

the dead. The annihilation opened up central Europe to the Muslims

and further weakened Constantinople.

In 1453 the Turks finally sacked Constantinople, news of which

terrified European leaders. Pope Nicholas V tried to organise

a crusade to recover the city, but it was yet another failure.

Pope Callistus III did manage to organise one, funded by the

sale of indulgences, but it was diverted and finished up attacking

Genoa. Pope Pius II was so keen to revive the Crusades that

he went himself, but hardly anyone else could be coerced into

going with him. He waited near the coast at Ancona in the summer

of 1464, hoping for others to turn up. His attendants concealed

the fact that no supporting armies were on the way, and drew

the curtains of his litter so that he should not see the desertions

from his own fleet. When a few Venetian galleys hove into sight

His Holiness died, apparently of excitement, and the crusade

was promptly abandoned.

When Columbus sailed to the americas in 1492 he wrote to their

Catholic Majesties, Ferdinand and Isabella, "I propose

to your Majesties that all the profit derived from this enterprise

be used for the recovery of Jerusalem". Crusades were still

regarded as desirable and possible. Their Catholic Majesties'

grandson, the Emperor Charles V, also talked of Crusades - he

was after all the titular King of Jerusalem - and his crusader

talk was taken seriously enough for Suleiman to rebuild the

walls of Jerusalem. Over the next three centuries, further attempts

were made at organising a crusade, but nothing came of them.

Repercussions

The object of the crusades had been to save Eastern Christendom

from the Muslims. They were undertaken with God's encouragement,

support and promise of victory. When they ended they had proved

a disastrous failure. The whole of Eastern Christendom was under

Muslim rule. The Crusades, especially the later ones, had been

characterised by partisan self-interest, short-sighted pettiness,

internal squabbles, strategic mismanagement, poor military leadership,

bigotry, barbarism, corruption and dishonour. The implications

were wide-ranging. The popes had succeeded in ruining the emperors

of both East and West, while strengthening and unifying disparate

Muslim enemies. The greatest Church in Christendom, Sancta Sophia,

was now a mosque. Many Eastern Churches, which had always enjoyed

toleration under Muslim rulers, now suffered persecution and

decline. The schism between East and West, which might have

been healed by allies in war, was instead made permanent. Asia

was lost to Christianity and was soon to convert wholesale to

Islam. The balance of world power had shifted irrevocably. The

death toll of these expeditions will never be known accurately

for either side, but it is certain that it numbered hundreds

of thousands, and possibly millions. Most of the dead were Christians.

In fact Christian forces themselves may have killed as many

Christians and Jews as they did Muslims. Repercussions

The object of the crusades had been to save Eastern Christendom

from the Muslims. They were undertaken with God's encouragement,

support and promise of victory. When they ended they had proved

a disastrous failure. The whole of Eastern Christendom was under

Muslim rule. The Crusades, especially the later ones, had been

characterised by partisan self-interest, short-sighted pettiness,

internal squabbles, strategic mismanagement, poor military leadership,

bigotry, barbarism, corruption and dishonour. The implications

were wide-ranging. The popes had succeeded in ruining the emperors

of both East and West, while strengthening and unifying disparate

Muslim enemies. The greatest Church in Christendom, Sancta Sophia,

was now a mosque. Many Eastern Churches, which had always enjoyed

toleration under Muslim rulers, now suffered persecution and

decline. The schism between East and West, which might have

been healed by allies in war, was instead made permanent. Asia

was lost to Christianity and was soon to convert wholesale to

Islam. The balance of world power had shifted irrevocably. The

death toll of these expeditions will never be known accurately

for either side, but it is certain that it numbered hundreds

of thousands, and possibly millions. Most of the dead were Christians.

In fact Christian forces themselves may have killed as many

Christians and Jews as they did Muslims.

Both sides fought fiercely, not to say barbarously. Christian

virtues such as mercy and cheek-turning had been almost totally

absent throughout, at least on the Christian side. At the end

of it all nothing positive had been achieved. Before the crusades,

Muslims had established a great reputation for tolerance. Now

that they had suffered Christian atrocities and perfidy, they

had become fanatical in defence of their religion. As Runciman

wrote of the slaughter at Jerusalem during the First Crusade:

"It was this bloodthirsty proof of Christian fanaticism

that recreated the fanaticism of Islam"*.

Muslim respect for Eastern Christians was superseded by hatred

and contempt for Western ones.

The bitterness that was generated between the Christian West

and the Muslim Levant was so great that its effects rumbled

down the centuries and echo to the present day. Across many

Eastern countries the word for a western foreigner is ferenghi,

a corruption of Frank, and an echo of the fact that crusaders

were usually referred to as Franks in the Middle Ages —

but this is far from the most serious reverberation from the

crusades.

Western Churchmen kept the crusader ideal alive. In the early

ninteenth century François-René, Vicomte de Chateaubriand

was inducted into the Order of the Holy sepulchre by Franciscans

in the sepulchre itself- knighting him with the first crusader

King of Jerusalem's sword.

Later In the nineteenth century the Crimean War was triggered

by Holy Russia declaring itself protector of Christians in Ottoman

lands. Czar Nicholas I saw himself "waging war for a solely

Christian purpose, under the banner of the Holy Cross".

He thought of the Christian God as the "Russian God"

and Russia as the successor of Constantinople. Moscow even called

itself the Third Rome, i.e. the third capital of the Empire.

Among others the new Rome sought to protect the Armenians, the

victims (as well as the perpetrators) of numerous atrocities

over the centuries. In 1915 Christian Armenians rebelled against

the Turks and massacred Muslims. At Van alone they were reported

to have killed 30,000. Over the next five years, hundreds of

thousands died. According to some the victims were mainly Christians,

according to others they were mainly Muslim. Such killing has

continued into recent times. In 1988 Christians and Muslims

started killing each other again, this time over the enclave

of Ngorno Karabakh in Azerbaijan.

When General Allenby took Jerusalem in 1917 he was careful

not to offend Christians by riding his horse into the city,

but he ws not as careful about Moslem sensitivities. When he

ceremonially accepted the keys to the city he is supposed to

have said "The Crusades have now ended", at which

the Mayor and Mufti stalked off. He went on to accept the keys

to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre from their Muslim custodians

giving them back with the words "Now the Crusades have

ended, I return to you the keys but these are not from Omar

or Saladin but from Allenby"*.

American millenarians also saw the taking of Jerusalem as the

triumph of the last Crusade. Many in the Middle East are familiar

with the story of the French General Henri Gouraud. After marching

into Damascus in July 1920 he is reported to have kicked Saladin's

tomb and said: "The Crusades have ended now! Awake Saladin,

we have returned! My presence here consecrates the victory of

the Cross over the Crescent.".

|

General Pershing's Crusaders in the 20th

Century shown on a US Government poster.

Note the ghostly medieval Crusader army riding alongside

Pershing's modern Crusader army

|

|

|

Many Muslims regarded the Anglo-French Suez expedition of 1956

as another attempted repeat of crusader victories of 1199. The

Palestine Liberation Organisation regards Israel as the West's

new crusader State.

|

American soldiers represented as Crusaders,

urged on by an angelic figure representing the USA, crucified

under the benign gaze of a Jesus

|

|

|

Christian-Muslim killing was not over. In the 1980s and 90s

Christian-Muslim fighting broke out in Africa, notably in Nigeria,

Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt. It happened in Europe as well —

in Bosnia and Kosovo. Christian forces were also heavily involved

in the civil war in the Lebanon. Arguably, the most brutal incident

during the whole war was perpetrated by Christians against Muslim

refugees. In 1982 hundreds of men, women and children were massacred

by Christian troops in the refugee camps in Sabra and Chatila.

It was like the original crusades all over again, except with

machine guns. Maronite Christians, who are in communion with

Rome, still emulate the behaviour of their crusader forbears.

When General Michel Aoun launched a Christian offensive in March

1989 against Syrians in the Lebanon, he explicitly called it

a "crusade". Some Muslim fighters in the Lebanon call

themselves Salabeyen after Saladin's men who fought

the crusaders.

There are many other echoes of the Crusades — louder in

the East than in the West. Two of the PLO's divisions are named

after the sites of Muslim victories over the Christian crusaders

(Hattin and Ayn Julat). Mehmet Ali Agca, who shot Pope John

Paul II in 1981, described his victim in a letter as the "supreme

commander of the Crusades"*.

During the Gulf war of 1991, Saddam Hussein was guaranteed massive

public support in many Muslim countries by likening the Western

offensive to a Christian crusade, and implicitly likening himself

to Saladin - that other famous native of Tikrit.

Following terrorist actions against the USA in 2001, President

George W. Bush characterised America's response by remarking

that "this crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take

a while" — thus opening up the whole issue of the

crusades again. Although the reference passed almost unnoticed

among Americans, it sounded to many Muslims like a call for

a holy war against Islam. In 2010 it was revealed that the US

were using gun sights produced by Trijicon Inc, a Michigan arms

company. These sights were stamped with biblical references

and widely used in Iraq and Afghanistan. The practice had been

started by the firm's founder, a devout Christian*.

Most people in countries such as the USA and UK are still unaware

of how sensitive the whole issue still is in the Muslim world.

Not so in Spain, where it is widely known that the train bombings

of 2004 were carried out in retribution for Spain's part in

the war in Iraq as well as the reconquista — the fifteenth

century Christian crusade against the moors of Iberia.

|

A large number of Christians on social

media see themselves as warriors for Christ.

|

|

|

The crusaders' cross is still remembered by Muslims and it

is for this reason that any symbol in the form of a red cross

is not acceptable in Muslim countries, even if it has no connection

with the crusaders' cross. The organisation generally known

in the west as the Red Cross is to Muslims known as the Red

Crescent. Nor is this the only symbolic reminder: Western swords

are still made in the shape of a cross, just as scimitars are

still made in the shape of a crescent.

More Christian Violence and Warfare

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

| |

| |

| More Books |

|

|

|