| |

|

|

When I was a child, I spake as a child,

I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when

I became a man, I put away childish things.

|

|

Corinthians 13:12

|

This case study is a little different. Here we will look at

how the mainstream Churches have changed their views, and why

they have changed their views, on the reliability of the Bible.

Porphyry (c.232-c.303) demonstrated that the book of Daniel

could not have been written when Jews and Christians claimed

it was. His works were later condemned and burned , and facts

he had unearthed were denied, then forgotten. Christian writings

attempting to refute his works were also burned, as even these

works were too compromising. Again, early Christians had been

well aware that the scriptures contradicted each other, but

this too was denied. Anyone who could read could see the contradictions

for themselves. For a long time laymen were not permitted to

learn to read, so there was little danger of them finding out

the truth. Those who let out the secret were dealt with. Those

outside the Church could expect death. Those inside could expect

the same, unless they were already respected scholars. Pierre

Abélard is perhaps the best known example. In the eleventh

century he was sentenced to life imprisonment for listing Church

contradictions in a work entitled Sic et Non (Yes

and No).

When humanist scholars returned to Hebrew and Greek texts of

the Bible, they discovered that many passages had been badly

misinterpreted. The authority of many medieval accretions was

destroyed, and this created a wave of reaction against the Church.

Humanists ridiculed the Church in works such as Sebastian Brandt's

Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools) of 1494, and

Erasmus's Moriae Encomium (In Praise of Folly)

of 1509. Written soon after the introduction of printing, such

works became best sellers, and their widespread popularity ensured

the life and liberty of their authors. Humanism and the revival

of learning would fuel the Reformation.

When Protestant Churches came into being, the Bible became

available to all, even in vernacular translations. Now it was

not only scholars who were aware of discrepancies and textual

irregularities in the Bible. By the seventeenth century men

of learning were starting to air the existence of contradictions

publicly. In his Leviathan, published in 1651, Hobbes

gave cogent reasons why Moses could not possibly have written

the whole of the Pentateuch. He risked his life in doing so.

A few years later, in 1679, a student at Edinburgh University

made the same assertion, along with other similar ones, and

was hanged for it. Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) risked persecution

by Jews and Christians when he pointed out biblical mistakes,

inconsistencies and impossibilities, thus denying the infallibility

of scripture. Newton doubted the authenticity of the New Testament

but chose to keep his views to himself.

In an academic study of 1711 a German minister, H. B. Witter,

disclosed his discovery that the Bible's account of the creation

was really two interwoven stories, written by different authors

and at different times (see page

30 ). In the 1720s Thomas Woolston was put under house arrest

for life, for voicing doubts about the Resurrection and other

biblical miracles. In 1753 Jean d"Astruc, a physician to

Louis XV, took Witter's ideas a stage further, revealing in

an anonymous booklet that different hands could be seen in the

book of Genesis. By the simple method of stripping out the text

in which the author referred to God as Jahveh, and

the text in which the author referred to him as Elohim,

is was possible to identify coherent strands that had been edited

together. Suddenly the duplication — two creations, two

accounts of the flood, and so on — made sense. Witter's

ideas rapidly gained acceptance among scholars.

A few years later Thomas Paine popularised the right to doubt

in England. In The Age of Reason he established that

the Old Testament books could not have been written by the authors

ascribed to them, that their chronologies were absurd, that

they contradicted themselves on many points, and that many of

the claims traditionally made for them were untenable. He purported

to show that the story of Jesus was false and that the canonical

gospels had not been written by their ascribed authors. He said

that the biblical story of Jesus had every mark of fraud and

imposition stamped upon the face of it. At the time Paine's

findings were denied, and he was considered a blasphemous atheist.

But now the facts were available to all, not just a closed circle

of scholars. People were teaching themselves to read specifically

so that they could read Paine's works for themselves.

By the end of the seventeenth century the genie was well and

truly out of the bottle. Protestant scholars were pioneering

new forms of biblical criticism, particularly in Germany, where

biblical scholarship was not under Church control as it was

elsewhere in Europe. H. S. Reimarus , Professor of Hebrew and

Oriental Languages at Hamburg, rejected the biblical miracle

stories, held that Jesus was a failed revolutionary, and deduced

that biblical authors were fraudulent. Such opinions were highly

controversial, and would have cost Reimarus his job if they

had been published during his lifetime.

Scholars started wondering who had written the Pentateuch if

it had not been Moses. J. G. Eichorn (1752-1827), a German Old

Testament scholar, confirmed d"Astruc's view that there

are two distinct strands in Genesis, a J strand where God is

called Jahveh, and an E strand where he is referred

to as Elohim. There were thus at least two authors.

Eichorn's work was fiercely rejected by theologians, and attempts

to have it translated into English were frustrated by Church

and university authorities. It was finally translated only in

the twentieth century.

By the end of the eighteenth century scholarly scepticism was

gathering pace, though scholars were still paying a high price

for their integrity. W. M. L. De Wette , a Berlin professor

in the first part of the nineteenth century, doubted biblical

miracles and regarded the stories of Jesus" birth and the

Resurrection as mythical. He was deprived of his professorial

chair. Around the same time F. C. Baur founded the Tübingen

School, which held that the New Testament was largely a second

century synthesis of ideas from Jewish followers of Peter and

gentile followers of Paul. In 1835 the first part of D. F. Strauss's

Leben Jesu (Life of Jesus) was published.

Comparing the gospel accounts, Strauss deduced that the miracle

stories were mythical, and that the gospel stories were not

eyewitness accounts, but later conflations of garbled traditions.

He was dismissed from his post at Tübingen University.

His colleagues, though sympathetic, dared not speak out for

fear of their own positions.

No matter how many teachers were dismissed, or professors deprived

of their chairs, the movement was now unstoppable. In the same

year the Berlin philologist Karl Lachmann argued that contrary

to Church teaching, the Mark gospel was an earlier work than

the Matthew gospel, a view that is now almost universally accepted.

By the 1880s Julius Wellhausen had identified the four main

strands running through the Pentateuch.

Closely related to textual analysis of the Bible was modernism.

Modernists accepted the fallibility not only of the Bible, but

also of other authorities, including tradition, councils and

popes.

Modernists were however still sincere Christians. Attempting

to salvage something from the consequences of their own scholarship

they advocated the reinterpretation of Church teachings. They

held that Christianity must be continuously revised in the light

of contemporary requirements and advances in scientific opinion.

As time went on, and scholarship became more refined, positions

veered ever further from traditional teaching. Albert Schweitzer

(1875-1965) believed Jesus to have been a badly mistaken man

whose crucifixion came as rather a nasty shock to him. Rudolf

Bultmann, Professor at Marburg between 1921 and 1951, saw almost

the whole of the New Testament as mythical. German Protestants

had to accommodate themselves to an entirely new theology where

the Bible was at best figurative rather than literal, and at

worst a mish-mash of various people's fantasies. Many scholars,

like D. F. Strauss, ended their lives no longer Christians at

all.

The position of the Church of England had been crystallised

soon after the Reformation. Its position on any matter of doctrine

that might have been in doubt was stated explicitly in the 39

Articles of Religion. The King's Declaration prefixing the Articles

specifically prohibited "the least difference from the

said Articles" and took pride that clergymen "all

agree in the true, usual, literal meaning of the said Articles".

Nevertheless, scepticism grew within the Church of England.

Many educated people, including at least one Archbishop of Canterbury,

had harboured doubts about the Trinity even in the seventeenth

century, but most kept their views to themselves*.

By the early eighteenth century Anthony Collins was able to

point out discrepancies between Old Testament prophecies and

their supposed fulfilment in the New*.

Widespread doubts were becoming publicly visible in the late

eighteenth century as more and more people read Thomas Paine.

By the nineteenth century a school of Modernists known as Neologians

flourished in Oxford. They survived through influential support

and a relatively liberal atmosphere. Even so, many clerics felt

obliged to leave the Church, even though it meant giving up

their university positions. Notable losses included Arthur Hugh

Clough (1848), J. A. Froude (1849) and Sir Leslie Stephen (1862).

The Professor of Theology at King's College, London lost his

chair in 1853 for making observations about eternity that now

seem particularly unremarkable*.

Neologians, or Broad Churchmen as they came to be known, became

ever more vocal. Their views seemed particularly threatening

after Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859.

In 1860 a collection of Essays and Reviews by Broad

Churchmen raised a storm of controversy, and two of its authors

were tried for heresy: one for denying the inspiration of scripture,

the other for denying eternal punishment. Five counts were upheld

in the ecclesiastical court (the Court of Arches), and sentence

passed, but the verdicts were overturned on appeal to the Judicial

Committee of the Privy Council. At around the same time the

Bishop of Natal in South Africa was also tried for heresy for

pointing out biblical contradictions, denying accepted authorship

and doubting eternal punishment. He was condemned, deprived

and excommunicated, but then acquitted on appeal to the Privy

Council.

The requirements of His Majesty's declaration had become untenable.

In 1865 an Act of Parliament, the Clerical Subscription

Act, decreed that the clergy were not to be bound by every

word of the 39 Articles, but that they should assent to their

general tone and meaning. The Church approved this in the following

year. It opened the door to questioning all of the Articles

openly, although the implicit understanding was that theologians

should do so only amongst themselves. It was a sort of open

secret among the educated classes that science had discredited

traditional teachings and that they could no longer be interpreted

literally. Yet it was not permissible to admit such a thing

openly. In the 1880s an eminent Scottish professor, William

Robertson Smith, was tried for contributing articles to the

Encyclopaedia Britannica that discussed Wellhausen's

discoveries and suggested the Bible could be analysed scientifically.

Smith won his case but lost his chair at Aberdeen University.

The fallibility of traditional Church teaching was still a

sort of open secret, and scholars were still expected to keep

quiet about certain matters in public. In the twentieth century

a number of leading churchmen caused uproar in the Church by

breaking this convention, for example by openly rejecting the

Virgin Birth, denying the Resurrection, and questioning whether

Christ had instituted the Eucharist at the Last Supper. Among

them have been E. W. Barnes, the Bishop of Birmingham, in 1947;

and J. A. T. Robinson, the Bishop of Woolwich, with his book

Honest To God in 1963. Robinson felt safe enough to

concede that "God is intellectually superfluous, emotionally

dispensable and morally intolerable". Later, numerous theologians

contributed to The Myth of God Incarnate in 1977; and

David Jenkins, Prince Bishop of Durham, made various pronouncements

throughout the 1980s on subjects such as his scepticism about

Jesus" physical Resurrection. In his 1998 book Why

Christianity Must Change or Die, John Spong Episcopal bishop

of Newark, New Jersey, dismissed the idea that Jesus was divine

and pointed out that the God that most traditional Christians

believe in is an ogre. Richard Holloway, Archbishop of Edinburgh,

published a book called Godless Morality in 1999, destroying

the myth that morality is a specifically Christian characteristic.

Each time there were excited calls for resignations, defrockings

and heresy trials. The furore was not so much over the ideas,

which were increasingly widely shared, but over the breaking

of the convention that the faithful masses should not be told

about scholarly opinion within the Church.

The experience of the Roman Church was somewhat different.

It was wary of allowing its scholars access to the opinions

of others because so many had so often defected in the past.

A number of crusaders, for example, had joined the Eastern Churches,

or converted to Islam, and preachers sent to convert heretics

were themselves frequently converted. Even senior churchmen

defected, most notably Bernardino Ochino (1487-1564). Ochino,

who had been head of the Capuchin Order, had been granted permission

to study Protestant books in order to refute them. In the course

of his studies he converted to Protestantism. A safer reaction

to the views of non-Catholics was to ignore them. Such views

were heretical, and no good could come from studying them. The

best safeguard was ignorance.

|

Traditionalist Catholics saw Modernism

as a dangerous heresy, its evil tentacles embacing schools,

churches, colleges and other Christian institutions. Cartoon

by Catholic cartoonist E J Pace (1880-1946)

|

|

|

Pope Clement XI, in his constitution Unigenitus of

1713, insisted that the reading of the holy scriptures was not

for everyone. Open debate was not for Roman Catholics. No matter

that the genie had been long gone, the Roman Church still hoped

to force the stopper back into the bottle. Cardinal Newman,

who regarded anyone who questioned the infallibility of the

Bible as being wicked at heart, kept his copy of Paine's The

Age of Reason locked up in a safe to protect his students.

Late in the nineteenth century Roman Catholic theologians became

aware of the spectacular progress in understanding of the origins

of the Bible that had been made by German Protestants. Catholic

scholars were being left far behind, as the Germans" critical

approach was almost universally accepted in academic circles

outside the Roman Church. The then Pope, Leo XIII, relented.

He permitted new research because he wanted Roman Catholic scholars

to be able to refute the views of Protestant ones. His hopes

misfired, for the more his theologians studied the Bible scientifically,

the less easy they found it to accommodate themselves to Roman

dogma.

A Roman Catholic Modernist movement soon created difficulties

throughout Europe. In England the Modernist George Tyrrell was

obliged to retire to the countryside after writing about Hell

in 1899. He was later expelled from the Jesuit order and excommunicated.

In France the threat to orthodoxy grew ever greater. Theological

books by Lucien Laberthonnière in 1903 and 1904 were

placed on the Index. Pierre Batiffol, who was associated with

the Modernists, was forced to resign as Rector of the Institut

Catholique at Toulouse in 1905, and his book on the Eucharist

was placed on the Index in 1911. Alfred Loisy, one of the leaders

of Roman Catholic Modernism in France, published works that

acknowledged that, far from being divine and infallible, the

Bible is full of errors. He doubted the Virgin Birth and the

authenticity of the John gospel. Five of his works were placed

on the Index in 1903-4, he lost his chair at the Institut

Catholique in Paris, and he was excommunicated in 1907,

along with Tyrrell.

|

The Catholic cartoonist E J Pace, perhaps

correctly, saw Modernism as the first step towards atheism.

In the cartoon below drawn in 1922 he intends to horrify

his readership by showing the steps from Christianity

to atheism. It is not obvious why "no diety"

appears before "agnosticism".

|

|

|

Modernism was in danger of running away with orthodoxy, and

had to be stopped. Pope Pius X condemned the Modernist movement

in the decree Lamentabili, as part of his attack on

theological novelties in 1907. He treated progress as something

akin to heresy. Soon afterwards a papal encyclical, Pascendi

dominici gregis, envisaged a massive conspiracy, inspired

by Protestants, to undermine the Roman Church. The Pope was

particularly opposed to the heresy of Americanism — a species

of Modernism that upheld democracy, progress, secular education

and unfettered reason. In 1910 Pius authorised a strong anti-Modernist

oath to be taken by all ministers and teachers. More writers

were excommunicated, and the Church was cleansed. Modernism

apparently disappeared from the Roman Church, and Roman Catholic

teaching was back in the Middle Ages. A Handbook of Heresies,

published some 20 years later and bearing the Roman Catholic

imprimatur, states the position as follows:

In the Catholic Church, true to the dogmatic principle taught

by the living Voice, Modernism could retain no foothold. Outside

the Unity it was far otherwise: in all sects, but especially

the Anglican Establishment, owing to her boast of comprehensiveness,

and to her purposely ambiguous formulas, modernism has triumphed.

One by one the old creeds, the old doctrines are restated,

re-interpreted, rejected. To-day there is no sect in Europe

of any size or standing that dares insist on the acceptance

of any dogma whatever — in its literal meaning —

as a condition of membership or even ministry. The Catholic

Church alone stands today as she has ever stood, judging —

not judged by — modern thought ...*

The position is not really quite so straightforward. For one

thing popes are still finding it necessary to censor clerical

opinion. Hans Küng, Edward Schillebeeckx and Leonardo Boff

have all been silenced for voicing opinions that differ from

the Pope's . The first woman to hold a chair of Roman Catholic

theology (Uta Ranke-Heinemann) had her teaching licence withdrawn

in 1987, after she questioned the Virgin Birth. On the other

hand, during the twentieth century the Roman Church has slowly

been doing what it always said it would never do, reconciling

itself to progress. Around the beginning of the 1980s, Pope

John Paul II finally acknowledged what Eichorn had known well

over a century before, that there are two distinct strands in

Genesis, a J strand where God is called Jahveh, and

an E strand where God is referred to as Elohim*.

If John Paul II had said this when he was a young priest, he

would never have been allowed a licence to teach theology, and

could have been excommunicated as a Modernist heretic. If he

had said it a few centuries earlier he would have been burned

at the stake. The fact is that the Roman Church shifts ground

just like the more liberal Churches — it is just that it

moves so slowly that not everybody notices.

Many biblical scholars now agree with Thomas Paine that the

biblical story of Jesus has every mark of fraud and imposition

stamped upon the face of it, and they may not have to wait long

before a pope agrees, although his wording may be a little more

diplomatic.

He who will not reason is a bigot; he who cannot is a fool,

and he who dare not is a slave. George Gordon, Lord Byron

(1788-1824)

There are still a few sensitive areas where Churches will try

to defeat science and scholarship by the traditional techniques

of interpreting and "losing" important evidence. We

have seen that traditionally the Church would destroy inconvenient

writings and replace them with its own forgeries. It cannot

hope to get away with forgeries in the twenty-first century,

but there is still scope for traditional methods of manipulation.

One such case in which the Roman Church has been involved is

that of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which have been described as the

most important archaeological discovery ever*.

In 1948 a number of ancient scrolls were discovered in a cave

in the Judæan hills, at a place called Qumran. More scrolls

were discovered buried in nearby caves. The scrolls dated from

before AD 70, most of them Old Testament biblical texts at least

1,000 years older than other known copies. There were also other

texts, previously unknown. The excavation of these scrolls was

overseen by Father Roland de Vaux, a Roman Catholic priest,

who taught at the Ecole Biblique et Archéologique,

a French Catholic Theological School in Jerusalem. This

institution was run by Dominicans, and had been established

in 1890, in accordance with the Church's then policy of using

biblical and archaeological studies to strengthen the faith.

Some of the scrolls disappeared, but others ended up in the

Rockefeller Museum, the Palestine Archaeological Museum in East

Jerusalem. A group of scholars was assembled to study the scrolls

under the leadership of de Vaux, almost all Christians, and

with a heavy concentration of Roman Catholics nominated by the

Ecole. No Jews were included, ostensibly for political

reasons, although the scrolls were clearly Jewish, and needed

a Jewish historian to set them in context. No atheists were

included, although one agnostic, John Allegro, was allowed access

to selected texts. De Vaux continued to refuse to allow any

Jews to work on the scrolls in the Rockefeller, even after Jerusalem

came under Israeli control in 1967.

It was soon apparent that the scrolls contained information

that did not fit well with Christian orthodoxy. In particular

the scrolls revealed that whoever occupied Qumran, they had

their own Davidic messiah, whom they regarded as a "son

of God" and as begotten of God. This text was not officially

published, although details were leaked and published in the

Biblical Archaeology Review in 1990*.

In other inconvenient texts, the word messiah is translated

as "thine anointed" apparently in order to disguise

its full import — exactly as earlier translators had done

with biblical texts. Also it came to light that the Qumran community

practised baptism, recognised 12 leaders based in Jerusalem,

and shared goods in common (cf. Acts 2:44-6). They also used

many phrases now regarded as characteristically Christian (such

as "followers of the Way" and "poor in spirit").

They also recognised a Teacher of Righteousness, echoing

a title accorded to Jesus" brother James and perhaps to

Jesus himself*. They ate

meals together, a priest blessing the bread and wine.

And when they gather for the Community table …and

mix the wine for drinking, let no man stretch forth his hand

on the first of the bread or the wine before the priest, for

it is he who will bless the first fruits of bread and wine…And

afterwards, the Messiah of Israel shall stretch out his hands

upon the bread.... *

Some passages link together and explain early Christian texts,

but these too were not published. Despite many striking similarities

between the community at Qumran and early Christianity, the

Roman Catholic Church scholars insisted that they were completely

different. De Vaux consistently misinterpreted evidence —

archaeological, numismatic, textual and palaeographological

in order to make the facts fit his preconceptions. Despite the

evidence he continued to hold that the site was occupied by

a peace-loving Essene community, and that it dated from a century

or two before Christian times. In fact there is good evidence

that Zealots occupied the site during and after the time of

Jesus. De Vaux and his fellow priests not only advocated their

own (objectively untenable) theory, but they also did their

best to discredit anyone who made alternative suggestions about

interpretation, virulently denouncing scholars like John Allegro,

Robert Eisenman and Edmund Wilson who pointed out that de Vaux's

team had interpreted the texts to suit their own religious beliefs.

Sometimes the team found it necessary to minimise the importance

of texts that do not conform to Roman Catholic preconceptions.

In a particularly striking example, de Vaux dismissed one scroll

(the important "copper scroll") as a mere fantasy,

claiming that it was of interest to historians of folk-lore,

and dismissing it as "a whimsical product of a deranged

mind".

A suspicious level of control was exercised in the allocation

of material, and some of it was kept secret. All fragments were

brought first to de Vaux or another Ecole nominee (Milik),

and complete secrecy was kept until they had had the opportunity

to study them*. By the

mid-1950s a gulf was opening up between John Allegro and other

members of the team. Allegro's objective assessments were not

at all to the liking of his Christian colleagues.

In 1956 de Vaux was appointed to the Pontifical Biblical Commission

, providing a direct chain of control from the Vatican. Since

1956 every director of the Ecole Biblique has also

been a member of the Pontifical Biblical Commission. The Church

seemed to be tightening its grip. By the end of 1957 Allegro

realised that "the non-Catholic members of the team are

being removed as quickly as possible.... "*.

Later he claimed that ".... de Vaux will stop at nothing

to control the scrolls material" and "I am convinced

that if something does turn up which affects Roman Catholic

dogma, the world will never see it. De Vaux will scrape the

money out of some other barrel and send the lot to the Vatican

to be hidden or destroyed.... "*.

Since the Catholic faction exerted total control, there is no

way of knowing whether Allegro was right. Many suspect that

inconvenient material was suppressed, in much the same way that

inconvenient material has been suppressed in previous centuries.

Access to the scrolls was allowed only to those who could be

trusted to promote the approved Church line. This seems to have

been one reason why Jewish scholars were denied access, despite

the fact that the scrolls were Jewish documents, written by

Jews for Jews. Ignorance of Judaism was no bar to being involved,

and dislike of Judaism appears to have been acceptable. John

Strugnell, who became head of the Qumran team in 1987, published

almost nothing of the mass of materials available to him. He

was unusually open about his views on Judaism, even if badly

mistaken about his facts. In a widely reported interview he

disclosed that Judaism is "a horrible religion. It's a

Christian heresy, and we deal with our heretics in different

ways"*. Apart from

any other implications, this did little to inspire confidence

in his scholarship, and particularly his understanding of the

relationship between Judaism and Christianity.

In the opinion of many, the secrecy surrounding the Dead Sea

Scrolls is an outrage*.

The scrolls were kept secret for decades by men with strong

religious convictions and a strong interest in maintaining Roman

Catholic orthodoxy whatever the objective evidence might be.

De Vaux never published a final report of the original excavations.

There has never been a full inventory of all the scrolls and

fragments , and some of the more interesting texts were published

after forty years only because they had been leaked. After half

a century, Allegro, the sole agnostic, was still the only scholar

to have published all of the material in his care. The failure

of the others is widely recognised as scandalous. Morton Smith,

Professor Emeritus of Religion at Columbia University, has described

the failure to publish the scrolls as "too disgusting"

even to talk about. Geza Vermes, Reader in Jewish Studies at

Oxford University, has called the secrecy about and excessive

control over the scrolls "the academic scandal par

excellence of the twentieth century".

There are other candidates for the title "the academic

scandal par excellence of the twentieth century",

including archaeological abuses. An example is the archaeology

carried out at St. Peter's Basilica, the church of the Vatican.

According to a late tradition Saint Peter was buried here. In

1939 an archaeological excavation in the grottoes below the

current Basilica uncovered Roman mausoleums from the necropolis.

In the area under the high altar, the excavators found a structure

resembling a temple that they named the aedicula (meaning little

temple). There, they allegedly found the tomb of St Peter. This

discovery lacks scientific credibility and a number of scholars

consider the findings fraudulent. Here are a few of the relevant

factors:

- The excavators were Jesuits

- Although it was already known that the basilica was built

on top of a large pagan necropolis on the Vatican Hill, but

no relevant independent experts with this specialism were

involved.

- the entire excavation was kept secret for 10 years.

- The excavation destroyed the aedicula floor. Inadequate

records were kept, so that it is impossible for independent

archaeologists to assess whether the findings are genuine

- the bones were found when the pope himself visited the excavation

- An independent scholar allowed to examine the bones was

only allowed to do so on condition that he did not publish

the results.

- The bones cannot all be Peter's, there are leg bones from

at least 5 separate legs. The bones also includes the remains

of farm animals.

- The arrangement of bones sounds distinctly unlikely for

the burial of an important Christian. The various bones, including

chicken bones, had been heaped together and piled under a

wall in an otherwise empty grave.

- Soil attached to the bones does not appear to match soil

in the grave.

- In 1942, the Administrator of St. Peter's, Monsignor Ludwig

Kaas,who oversaw the dig, but had no knowledge of archaeological

practice, secretly ordered some of the bones to be stored

elsewhere for safe-keeping.

- After Kaas's death, tests revealed that the remains belonged

to a man in his sixties. On the basis of this, Pope Paul VI

announced on June 26, 1968 ,that the relics of St. Peter had

been discovered. Antonio Ferrua, the leading archaeologist

at the excavation said that he was not convinced that the

bones that were found were those of St. Peter

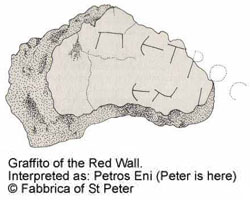

- There is no evidence that the grave was that of Saint Peter.

The identification is based on an incomplete graffito, one

possible meaning of which is "Peter is here". This

graffito is itself suspect, but even if it were genuine and

even if the incomplete text "...pet... en..." had

been correctly interpreted as, it could mean "Peter [the

graffiti artist] was here".

- The graffito was found after the bones, when Catholics were

looking for a connection to Peter.

- The graffito was found on a piece of plaster. There is no

photograph or other record of the location of the original

plaster. The plaster is a fragment which had allegedly broken

from a nearby wall. It is no longer possible to determine

where it came from.

The

Church still advertises the site as the tomb of Saint Peter.

Sceptical scholars suspect deliberate manipulation by someone

who did not think through the implications of their fraud. Sceptics

suggest that bones had been collected by the excavators from

around the necropolis, and grouped together by Jesuits or Vatican

officials, the graffito having also been found elsewhere, and

possibly chipped to leave a few words that can be interpreted

as meaning that Peter was nearby. By doing this, the Jesuits

would be relieved of the embarrassment of a Pagan temple directly

under the high alter of Saint Peter's Basilica, and furnished

with evidence of the existence of the man they regard as the

first pope. The sceptics' case is bolstered by the fact that

the Vatican has still not permitted a proper independent scientific

investigation of the evidence. The

Church still advertises the site as the tomb of Saint Peter.

Sceptical scholars suspect deliberate manipulation by someone

who did not think through the implications of their fraud. Sceptics

suggest that bones had been collected by the excavators from

around the necropolis, and grouped together by Jesuits or Vatican

officials, the graffito having also been found elsewhere, and

possibly chipped to leave a few words that can be interpreted

as meaning that Peter was nearby. By doing this, the Jesuits

would be relieved of the embarrassment of a Pagan temple directly

under the high alter of Saint Peter's Basilica, and furnished

with evidence of the existence of the man they regard as the

first pope. The sceptics' case is bolstered by the fact that

the Vatican has still not permitted a proper independent scientific

investigation of the evidence.

A great deal of intellectual dishonesty is evidenced in the

history of Christianity. This dishonesty seems to have continued

from the earliest times to the present day. Why should any organisation

have engaged in such extensive forgery, destruction and manipulation?

Why have honest scholars been persecuted for 2,000 years whenever

they have pointed out a problem? And why has it been necessary

to shift ground so radically — so radically that bishops

and popes now hold beliefs that were previously so heretical

that people were burned alive for holding them?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

| |

| |

| More Books |

|

|

|