| |

|

|

I never saw, heard, nor read that

the clergy were beloved in any nation where Christianity

was the religion of the Country. Nothing can render

them popular but some degree of persecution.

|

|

Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), Thoughts

on Religion

|

Anyone who has benefited from a conventional Western education

will be familiar with the dreadful persecutions endured by untold

numbers of early Christians. According to the conventional story

these early Christians were meek and innocent, and invariably

went to the lions with extraordinary bravery inspired by their

great faith. For their part, the Roman oppressors were brutal

and merciless, and killed the unfortunate Christians for no

better reason than that they chose a new and harmless faith.

Yet even these heartless pagans could not help but be impressed

by the fortitude of their victims. The steadfast courage of

Christians as they were torn to shreds by wild animals in the

Coliseum was astonishing to all who witnessed it.

|

Detail from The Christian Martyrs' Last

Prayer by Leon Gerome (1824–1904)

This is a nineteenth century fantasy painting, commissioned

William T. Walters of Baltimore in 1863

|

|

|

Enjoyable as the story is, it is flawed in almost every respect,

a fact that has been known to scholars for many centuries, and

to the educated classes at least since the publication of The

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in the last quarter

of the eighteenth century. Religious persecution was virtually

unknown in the ancient world. The Romans especially were universally

tolerant. Their principal reactions to the religions of others

were interest and occasional amusement. Their toleration did

not extend to cults that acted merely as a cover for sedition

or criminality, but all genuine faiths were respected and protected.

As far as we know, no one in the classical world hit upon the

idea of exterminating others because of the god they chose to

worship1. As

Gibbon put it, quoting Seneca the Younger: "The various

modes of worship which prevailed in the Roman world, were all

considered by the people as equally true, by the philosopher

as equally false, and by the magistrate as equally useful. And

thus toleration produced not only mutual indulgence, but even

religious concord"2.

|

Third-century AD mosaic in the Museum

of El Djem (Tunisia).

This image is often used as an example of how Christians

were martyred in the Coliseum. The truth is that we have

not a single example of Christians being killed in the

Coliseum in this way. This image shows the punishment

of Damnatio ad bestias by which the worst criminals

were executed.This mode of execution was used under a

long line of Christian Emperors. The practice of damnatio

ad bestias was abolished in Rome only in 681 AD. It

was used after that in the Byzantine Empire. The bishop

of Saare-Lääne was sentencing criminals to

damnatio ad bestias at the Bishop's Castle in modern

Estonia into the Middle Ages.

|

|

|

How strict the Roman principle of tolerance was is illustrated

by the Roman attitude to the Jews, the sole dissenters from

the religious harmony of the ancient world. Gibbon noted of

Jewish beliefs that "according to the maxims of universal

toleration, the Romans protected a superstition which they despised"3.

Soldiers were transferred or executed for offending Jewish sensibilities.

Legions by-passed Judæa to avoid offence by carrying the

imperial portraits on their standards across Jewish soil. The

Judæan coinage was unique within the Roman provinces in

that it did not bear the Emperor's face, again because of Jewish

sensibilities. In place of emperor worship, the Jews were permitted

to show their respect for the State by offering sacrifices on

behalf of the Emperor. Jews could become full Roman citizens

— Paul of Tarsus was one of many. All in all, the Romans

were flexible and tolerant.

There was no obvious reason why Christians should not have

been tolerated as the Jews were, and yet they were not. Christians

seem to have provoked a great deal of hostility and to have

made themselves outstandingly unpopular. Tacitus wrote around

AD 110 that they were "notoriously depraved". Nero,

he noted, had arrested Christians in Rome for arson and for

other antisocial behaviour4.

Suetonius (AD 70-160) recorded that Claudius expelled them from

Rome for causing continual disturbances5.

Because of widespread misgivings about them, Pliny the Younger

made enquiries but found only squalid superstition carried to

great length6.

One way or another Christians made enemies everywhere. Some

Christian leaders, like Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, noted that

Christians deserved the treatment they were getting7.

The philosopher Celsus disapproved of their intolerance. In

248 Origen noted that hostility to the Church was increasing

rapidly. Soon the citizens of Antioch were asking that Christians

be forbidden from living in their city8.

The citizens of Nicomedia made similar requests9,

and so did other cities.

In 312 the Emperor Maximin Daia was being petitioned to suppress

the disloyal Christians10.

Despite popular dislike of the Christians, the authorities were

generally still tolerant. In response to Pliny's requests for

guidance the Emperor Trajan advised moderation. There should

be no general inquisition. Anonymous accusers should be ignored,

and accusations made by responsible citizens should be properly

investigated.

Christians were sporadically investigated by the authorities,

mainly because they were believed to have been promoting sedition.

They seem to have been unnecessarily secretive and did little

or nothing to counter beliefs that they opposed the established

government, apparently because they did oppose the established

government. They reviled the Imperial capital, referring to

it as the Whore of Babylon. They looked forward to

its destruction (as in Revelation 14:8). They prayed for the

end of the world: "Let grace come and let this world pass

away"11.

Indeed it was widely believed that they tried a number of times

to ignite fires that would destroy the world and hasten the

coming of their new kingdom.

Christians were also accused of cannibalism and incest. The

charge that they ate human flesh might well have arisen through

misinterpretations of the Lord's Supper. Had not their dead

leader claimed that "Except ye eat the flesh of the Son

of man, and drink his blood, ye have no lifein you" (John

6:53)? If the charge was mistaken, then the mistake could easily

have been explained. Instead, accused Christians refused to

explain their practices or to refute stories that they ate children

at their ceremonies. Some declined to answer any questions at

all — even refusing to give their names or nationalities12.

Sometimes they lied, for example claiming to be Old Testament

characters like Elijah or Daniel. They also refused to take

oaths.

No

doubt the accusations of cannibalism were mistaken, but Christians

were certainly guilty of other crimes. Infused with the truth

of their own religion they were openly hostile to the religions

of others, in a manner frequently amounting to criminal behaviour.

They reviled the Roman and other gods,

razed temples, set fires, vandalised sacred sites, destroyed

images, and incited riots. Since Christians considered vandalism

directed at the holy places of other religions to be entirely

justifiable, they did not seek to conceal it once they came

to power. When Christians were executed for vandalism or arson,

their fellow believers openly acclaimed them as martyrs and

saints. According to Christian martyrologies Theodore of Amasea

(aka St. Theodore Tyro) was a soldier in the Roman Army at Pontus

on the Black Sea. He became a Christian, deserted from the army

and set fire to the temple of Cybele near Amasea in Pontus.

For this he was executed, and is now acclaimed as a martyr and

a saint. Christian hagiographies claim that Saint Martin of

Tours (a soldier charged with cowardice, who either deserted

or was cashiered from the Roman army) was another prolific arsonist,

causing his followers to destroy countless non-Christian holy

places. He ordered the destruction of temples, altars and sculptures

in Gaul. Gibbon tells us of Martin and another fanatical Christian

saint in Chapter XXVIII of his Decline and Fall of the Roman

Empire. No

doubt the accusations of cannibalism were mistaken, but Christians

were certainly guilty of other crimes. Infused with the truth

of their own religion they were openly hostile to the religions

of others, in a manner frequently amounting to criminal behaviour.

They reviled the Roman and other gods,

razed temples, set fires, vandalised sacred sites, destroyed

images, and incited riots. Since Christians considered vandalism

directed at the holy places of other religions to be entirely

justifiable, they did not seek to conceal it once they came

to power. When Christians were executed for vandalism or arson,

their fellow believers openly acclaimed them as martyrs and

saints. According to Christian martyrologies Theodore of Amasea

(aka St. Theodore Tyro) was a soldier in the Roman Army at Pontus

on the Black Sea. He became a Christian, deserted from the army

and set fire to the temple of Cybele near Amasea in Pontus.

For this he was executed, and is now acclaimed as a martyr and

a saint. Christian hagiographies claim that Saint Martin of

Tours (a soldier charged with cowardice, who either deserted

or was cashiered from the Roman army) was another prolific arsonist,

causing his followers to destroy countless non-Christian holy

places. He ordered the destruction of temples, altars and sculptures

in Gaul. Gibbon tells us of Martin and another fanatical Christian

saint in Chapter XXVIII of his Decline and Fall of the Roman

Empire.

In Gaul, the holy Martin, bishop of Tours, marched at the

head of his faithful monks to destroy the idols, the temples,

and the consecrated trees of his extensive diocese; .... In

Syria, the divine and excellent Marcellus, as he is styled

by Theodoret, a bishop animated with apostolic fervor, resolved

to level with the ground the stately temples within the diocese

of Apamea. ... Elated with victory, Marcellus took the field

in person against the powers of darkness; a numerous troop

of soldiers and gladiators marched under the episcopal banner,

and he successively attacked the villages and country temples

of the diocese of Apamea. ... A small number of temples was

protected by the fears, the venality, the taste, or the prudence,

of the civil and ecclesiastical governors. The temple of the

Celestial Venus at Carthage, whose sacred precincts formed

a circumference of two miles, was judiciously converted into

a Christian church; and a similar consecration has preserved

inviolate the majestic dome of the Pantheon at Rome. But in

almost every province of the Roman world, an army of fanatics,

without authority, and without discipline, invaded the peaceful

inhabitants; and the ruin of the fairest structures of antiquity

still displays the ravages of those [Christian] Barbarians

...

Surviving

accounts of martyrdom, even though they are fictitious, tell

us how Christians were expected to behave, and how pagan rulers

might react. These stories are revealing. Here for example is

the story of the martyrdom of the fictitious Saint Christopher

from The Passion of St. Christopher (BHL 1764), before he became

a giant, in later accounts. He arrived in Antioch, from a distant

land, with a dog's head and boars' tusks [sic]. Having been

miraculously provided with the ability to speak a language he

did not know, the first thing he does is to publicly describe

the Roman gods as cursed demons [2]. He then claims in front

of soldiers that he is suffering under a "tyrant"

[5] - even though he has only just arrived - and says that the

soldiers' father [presumably meaning the King] is Satan. The

solders offer to let him rest [6], but he wants no delay and

says to them, "Let us go to the king, therefore, that we

might receive a better crown [of martyrdom]." [8]. When

Christopher sees the king he addresses him "O most unfortunate

and corrupt king". [9]Refusing to worship he says "Do

what you want, then: for I will not offer sacrifice to the demons

who are deaf, just as you yourself are also deaf." [9]

The king now tries to convert Christopher with the help of a

couple of prostitutes, but Christopher turns the tables and

converts one of them, Gallenice, so that she can tortured and

martyred.[14]. The other, Aquilina, also converts and seeks

her own death. The kings begs her to "take pity on yourself",

but she is determined. She topples over and breaks into pieces

statues of Jupiter, Apollo and Hercules [16]. As a result she

is tortured and executed [18]. Christopher brought again before

the king, now induces the soldiers to desert and be martyred.

Christopher addresses the king as "Demon of many forms,

son of Satan" [22]. The King tries to have Christopher

burned alive, but instead, by God's will, 30 houses and many

pagans are burned alive [23] causing 10,000 people to convert

[24]. After some more miracles the King summons Christopher

again, and Christopher now addresses him as "Inventor of

every wickedness, disciple of the devil, partner in eternal

damnation," The King finally sentences him to death, after

which a great earthquake, kills the crowd then present. [27]

after which Christopher achieves the martyrdom he had worked

so hard for [27]. Surviving

accounts of martyrdom, even though they are fictitious, tell

us how Christians were expected to behave, and how pagan rulers

might react. These stories are revealing. Here for example is

the story of the martyrdom of the fictitious Saint Christopher

from The Passion of St. Christopher (BHL 1764), before he became

a giant, in later accounts. He arrived in Antioch, from a distant

land, with a dog's head and boars' tusks [sic]. Having been

miraculously provided with the ability to speak a language he

did not know, the first thing he does is to publicly describe

the Roman gods as cursed demons [2]. He then claims in front

of soldiers that he is suffering under a "tyrant"

[5] - even though he has only just arrived - and says that the

soldiers' father [presumably meaning the King] is Satan. The

solders offer to let him rest [6], but he wants no delay and

says to them, "Let us go to the king, therefore, that we

might receive a better crown [of martyrdom]." [8]. When

Christopher sees the king he addresses him "O most unfortunate

and corrupt king". [9]Refusing to worship he says "Do

what you want, then: for I will not offer sacrifice to the demons

who are deaf, just as you yourself are also deaf." [9]

The king now tries to convert Christopher with the help of a

couple of prostitutes, but Christopher turns the tables and

converts one of them, Gallenice, so that she can tortured and

martyred.[14]. The other, Aquilina, also converts and seeks

her own death. The kings begs her to "take pity on yourself",

but she is determined. She topples over and breaks into pieces

statues of Jupiter, Apollo and Hercules [16]. As a result she

is tortured and executed [18]. Christopher brought again before

the king, now induces the soldiers to desert and be martyred.

Christopher addresses the king as "Demon of many forms,

son of Satan" [22]. The King tries to have Christopher

burned alive, but instead, by God's will, 30 houses and many

pagans are burned alive [23] causing 10,000 people to convert

[24]. After some more miracles the King summons Christopher

again, and Christopher now addresses him as "Inventor of

every wickedness, disciple of the devil, partner in eternal

damnation," The King finally sentences him to death, after

which a great earthquake, kills the crowd then present. [27]

after which Christopher achieves the martyrdom he had worked

so hard for [27].

This story is entirely typical - a wish for death, abuse of

the authorities, pagan pleas for Christians to have mercy on

themselves, mass conversions and martyrdoms, the miraculous

killing of countless pagans, miracles, large fires, the destruction

of temples or statues, and finally the desired martyrdom of

the protagonist. Tucked away in these stories are some enticing

elements that hint at the nature of true "martyrdoms".

We know from independent records that Christians sought their

own martyrdom. We know that rulers begged them to have mercy

on themselves. We know that Christians destroyed temples and

statues. We know that Christians were frequently accused of

arson. In fact, apart from the miracles, both sources tell the

same story: how some Christians sought and finally achieved

their own deaths.

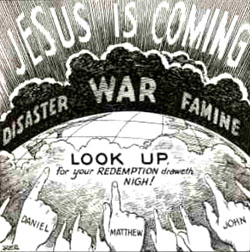

Christian

crimes such as arson seem to have been motivated by apocalyptic

literature like the Book of Revelations. The idea was that they

could trigger not just the destruction of Rome but the end of

the world, and hence the promised day of Judgement which would

ensure their place in heaven. (If this sounds improbable then

it is worth bearing in mind that there are many Christians today

in the USA, including influential politicians, who hold almost

identical views. So called “End-Timers” will freely

admit that they seek to trigger a Third World War, since this

will, they believe, herald the End of the World, and the consequent

Day of Judgement.) Christian

crimes such as arson seem to have been motivated by apocalyptic

literature like the Book of Revelations. The idea was that they

could trigger not just the destruction of Rome but the end of

the world, and hence the promised day of Judgement which would

ensure their place in heaven. (If this sounds improbable then

it is worth bearing in mind that there are many Christians today

in the USA, including influential politicians, who hold almost

identical views. So called “End-Timers” will freely

admit that they seek to trigger a Third World War, since this

will, they believe, herald the End of the World, and the consequent

Day of Judgement.)

The

Romans thought Christians were atheists. They denied the gods

and were known to revere a condemned criminal who had been executed

for his opposition to the state. They declined to acknowledge

the head of state, refusing to refer to Caesar by his honorific

Lord. For them Jesus was the only Lord and

the only ruling monarch13.

People believed that this sort of disrespect angered the gods.

The gods sent famines, droughts and plagues to punish the Empire

for allowing such blasphemy. By the fourth century the phenomenon

was proverbial: "no rain because of the Christians". The

Romans thought Christians were atheists. They denied the gods

and were known to revere a condemned criminal who had been executed

for his opposition to the state. They declined to acknowledge

the head of state, refusing to refer to Caesar by his honorific

Lord. For them Jesus was the only Lord and

the only ruling monarch13.

People believed that this sort of disrespect angered the gods.

The gods sent famines, droughts and plagues to punish the Empire

for allowing such blasphemy. By the fourth century the phenomenon

was proverbial: "no rain because of the Christians".

Christianity defeated and wiped out the old faith of the

pagans. Then with great fervour and diligence it strove to

cast out and utterly destroy every last possible occasion

of sin; and in doing so it ruined or demolished all the marvelous

statues, besides the other sculptures, the pictures, mosaics

and ornaments representing the false pagan gods; and as well

as this it destroyed countless memorials and inscriptions

left in honor of illustrious persons who had been commemorated

by the genius of the ancient world in statues and other public

monuments….their tremendous zeal was responsible for

inflicting severe damage on the practice of the arts, which

then fell into total confusion.

Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), Lives of the Artists.

|

Saint Aemilianus, known for his destruction

of ancient temples and libraries

Here he is shown using ropes to pull down a statue.

His followers are breaking up statues with picks and axes.

|

|

|

Christians were not only cultural vandals, perjurers and blasphemers;

they were also treasonable army deserters (like Theodore of

Amasea and Martin of Tours). As Robin Fox Lane, a prominent

Oxford historian, notes of the supposed persecutions prompted

by an edict of the Emperor Gallienus:

We know of at least one martyrdom which followed its despatch,

but it occurred in a province which was not at first under

Gallienus's control: otherwise, we have no knowledge of martyrdoms,

as opposed to Christian fictions of them, between 260 and

the 290s. When we find Christians being martyred, they are

soldiers in the army. The charge against them is not their

religion and their refusal to sacrifice, but their refusal

to serve in the ranks, an offence which was punishable on

other grounds14.

Christian leaders actively encouraged soldiers to desert from

the army. So all in all there was plenty of evidence that Christians

were seditious. They did little or nothing to counter the charge,

again apparently because it was true. Paul himself had been

accused not only of stirring up trouble but also of offending

against Caesar (Acts 25:8). The fact that Christians posed a

threat to public order is demonstrated by an imperial decree

that they might practise their faith unmolested as long as they

were not "scheming against the Roman Government" and

according to another decree "on condition that they do

nothing contrary to public order"15.

Christians were widely hated and became the victims of mob violence

throughout the Empire. It cannot have been surprising in view

of their open displays of disloyalty and hostility to the state,

their trouble making, their arson and vandalism, and their refusal

to refute a range of charges from sedition to baby-eating. There

must also be a suspicion that Christians were adept at murdering

their enemies. Time and time again surviving records boast of

the untimely deaths of these enemies. They died in agony with

their insides mysteriously eaten away, they unexpectedly committed

suicide in private, or they somehow toppled over cliffs. Invariably

these deaths are explicitly or implicitly attributed to God

by Christian chroniclers. Those who do not believe in murder-miracles

might suspect that God enjoyed the benefit of his followers'

assistance.

Despite all this, the persecution of Christians was slight,

intermittent, and limited geographically. Moreover it was not

religiously motivated. The authorities were invariably cautious

about proceeding against Christians. In the few cities where

they were thought to pose a threat only a few of those suspected

were charged. Not all of those were indicted. Of those indicted,

not all were convicted, while those who were convicted were

generally imprisoned or exiled, many subsequently being reprieved

under the terms of amnesties. It is certainly true that criminals

were torn apart by animals in the Coliseum in front of an audience,

but we have not a single account of an innocent Christian, or

indeed any Christian at all being fed to the lions there. The

familiar Christian stories of pagan audiences baying for innocent

Christian blood is pure fantasy. Most of this fantasy dates

from the Middle ages, and is marked by anachronism, self contradiction

and stereotyped sadomasochistic

themes.

Despite their crimes, ancient rights of sanctuary were extended

to the most guilty Christians. Under Roman law all burial places

were regarded as sacrosanct, so all Christian criminals enjoyed

inviolable sanctuary in the catacombs.

If we look at those who are generally held responsible for

the persecution of Christians we encounter another surprise.

Instead of bloodthirsty monsters we find men of culture and

moderation. The emperor most usually cited as a bloodthirsty

monster, Diocletian, turns out to have been a humane, prudent,

and magnanimous statesman, whose reign, as Gibbon pointed out,

was more illustrious than that of any of his predecessors16.

For most of his reign the Christians appear to have suffered

no persecution at all, and one cannot help but wonder what happened

towards the end of his reign to excite his displeasure. In his

most savage persecution Diocletian was responsible for perhaps

2,000 Christian deaths throughout the known world, though this

may be an overestimate. To put things in scale it might be noted

that in centuries to come Christian churchmen would be responsible

for the deaths of ten times as many Christians in a single city

in a single day17.

title="Saint Ignatius: martyr of suicide?"

title="Saint Ignatius: martyr of suicide?" A

major reason for the execution of Christians in Roman times

was that they actively sought their own deaths. They believed

that martyrdom guaranteed immediate and automatic admission

to Paradise. As Eusebius

said, they despised this transient life18.

Many of them therefore sought their complimentary ticket to

the hereafter — "glorious fulfilment" Eusebius

called it19.

Christians spoke of winning the crown of martyrdom,

as though death was the ultimate prize. Ignatius

of Antioch., a famous early martyr, who won his crown early

in the second century, would probably have been released if

he had wanted to be. He begged the church at Rome not to intervene

with the authorities on his behalf. In a letter to them he said

"it is going to be very hard to get to God unless you spare

me your intervention" (Ignatius's Letter to the Romans

1 ). He was yearning for death with all the passion of a lover

(Romans 7 ) and he wanted no more of what men call life (Romans

8 ). He mentioned his yearning for death in another letter,

and said that he was praying for combat with the lions (Letters

to the Trallians 4 and 10). His death wish shines through all

his surviving letters. So does his delight at being bound in

chains during his journey to execution. He clearly sees himself

as a sacrifice (Romans 4), and in another letter considers himself

invested with a title worthy of a god (Letter to the Magnesians

1). We do not know what he did to warrant his arrest, but we

do know that he wanted to die. Yet the modern Church regards

him not as a suicide, but as a saint. A

major reason for the execution of Christians in Roman times

was that they actively sought their own deaths. They believed

that martyrdom guaranteed immediate and automatic admission

to Paradise. As Eusebius

said, they despised this transient life18.

Many of them therefore sought their complimentary ticket to

the hereafter — "glorious fulfilment" Eusebius

called it19.

Christians spoke of winning the crown of martyrdom,

as though death was the ultimate prize. Ignatius

of Antioch., a famous early martyr, who won his crown early

in the second century, would probably have been released if

he had wanted to be. He begged the church at Rome not to intervene

with the authorities on his behalf. In a letter to them he said

"it is going to be very hard to get to God unless you spare

me your intervention" (Ignatius's Letter to the Romans

1 ). He was yearning for death with all the passion of a lover

(Romans 7 ) and he wanted no more of what men call life (Romans

8 ). He mentioned his yearning for death in another letter,

and said that he was praying for combat with the lions (Letters

to the Trallians 4 and 10). His death wish shines through all

his surviving letters. So does his delight at being bound in

chains during his journey to execution. He clearly sees himself

as a sacrifice (Romans 4), and in another letter considers himself

invested with a title worthy of a god (Letter to the Magnesians

1). We do not know what he did to warrant his arrest, but we

do know that he wanted to die. Yet the modern Church regards

him not as a suicide, but as a saint.

Other Christians also committed public suicide, vying to kill

themselves before anyone else did. At Alexandria an old woman

called Apollonia voluntarily jumped into a fire and was burned

to ashes20.

At Nicomedia "men and women alike leapt on to the pyre

with an inspired and mystical fervour"21.

Fellow martyrs must have sought their deaths even more fervently,

for in the early centuries the Church criticised many of its

own number as suicides. So did non-Christians. For Romans, suicide

was generally an honourable death if carried out with discretion.

No one thought less of Seneca, for example, because he took

his own life. The Emperor Marcus Aurelius (AD 121-180) had no

objection to suicide in principle, but he found the Christian

examples vulgar and theatrical. The Roman authorities begged

accused Christians to spare themselves. Judges tried to find

reasons not to execute them. They were allowed to relent and

save their lives right up to the last moment. Some did. Possibly

most did. But a few fervent ones would be satisfied with nothing

short of their crown of martyrdom.

The death of Polycarp, a Bishop of Smyrna (modern Izmir) in

AD 155 or 156, is well known to modern Christians but the circumstances

are not quite so well known. His crimes, including the destruction

of sacred images, were sufficient to incite the "whole

mass of Smyrnaeans, gentiles and Jews alike" to boil with

anger. According to Eusebius

he was burned alive in order to fulfil a prophecy revealed to

him in a dream. The Smyrnaeans were sufficiently generous to

play their part in its fulfilment22.

A little earlier a Christian called Germanicus had faced death

there. The governor urged him to have pity on his own youth,

but Germanicus desired a speedy release from this world. He

was faced with savage beasts, and when they failed to attack

him he dragged one of the animals towards him, and goaded it,

no doubt with the required result23.

Origen, destined to become a Church Father, craved martyrdom

as a boy. His fervour cannot have been as vigorous as that of

others, for it was frustrated by his mother's expedient of hiding

his clothes. Still, the young Origen

played his part and sent letters to his father encouraging him

to face a martyr's death instead24.

His father did die, leaving a destitute widow and seven children,

whereupon the eldest child, the divinely inspired 17-year-old

Origen, now the head of the household, left home and got himself

adopted by a rich female heretic. After this, as a teacher,

he inspired a clutch of his pupils to embrace martyrdom as well

Somehow Origen never quite got round to winning his own crown

of martyrdom.

Those

who witnessed Christian martyrdom-suicides were bewildered and

horrified by the Christian desire for death. Perpetua and her

pregnant slave Felicity were two Christian women driven by this

desire. Romans were too civilised to kill pregnant women, so

Felicity was obliged to live. She was delighted when she gave

birth prematurely, since the birth meant that she could now

win her crown of martyrdom25.

The two women succeeded in securing their deaths in Carthage

in AD 203, Felicity's breasts still wet with milk for her new-born

infant. Christians were impressed. Others were appalled. A few

years earlier a group of Christians had approached a proconsul

in Asia, asking him to have them killed. "Unhappy men!"

he said "if you are thus weary of your lives, is it so

difficult to find ropes and precipices?"26

Neither are these isolated incidents. There were numerous cases

of Christians, alone or in groups, explicitly asking to be martyred,

sometimes turning up with their hands already bound27.

It is hardly surprising that pagans dumped the bodies of Christian

"martyrs" in the same place as other suicides27a

- they presumably failed to notice any distinction. Those

who witnessed Christian martyrdom-suicides were bewildered and

horrified by the Christian desire for death. Perpetua and her

pregnant slave Felicity were two Christian women driven by this

desire. Romans were too civilised to kill pregnant women, so

Felicity was obliged to live. She was delighted when she gave

birth prematurely, since the birth meant that she could now

win her crown of martyrdom25.

The two women succeeded in securing their deaths in Carthage

in AD 203, Felicity's breasts still wet with milk for her new-born

infant. Christians were impressed. Others were appalled. A few

years earlier a group of Christians had approached a proconsul

in Asia, asking him to have them killed. "Unhappy men!"

he said "if you are thus weary of your lives, is it so

difficult to find ropes and precipices?"26

Neither are these isolated incidents. There were numerous cases

of Christians, alone or in groups, explicitly asking to be martyred,

sometimes turning up with their hands already bound27.

It is hardly surprising that pagans dumped the bodies of Christian

"martyrs" in the same place as other suicides27a

- they presumably failed to notice any distinction.

Even including suicides the number of those executed was not

great. Reliable numbers are hard to come by, but where they

are available they are low. Eusebius

described a mere 146 of them in the whole Empire, and some of

those sound rather fanciful to modern ears. Polycarp, the Episcopal

vandal already mentioned — "destroyer of our gods"

— became the twelfth martyr in Smyrna in the middle of

the second century28.

This number included martyrs from nearby Philadelphia (modern-day

Alaşehir), and may well have included genuine criminals

as well as suicides. The Church Father Origen stated openly

that few Christians had died for their faith. They were he said

"easily counted"29.

The fact is that we do not know how many Christians died during

the persecutions of the first few centuries. In all probability

they numbered only a few thousand. If we discount those who

were genuinely guilty of sedition, those who chose not to mount

a defence, and those who actively sought their own deaths, we

may not have any real martyrs left at all. For centuries, Christian

suicides continued to be hailed as martyrs. Thomas Becket is

one of many examples30.

In any case it is certain that in total the number of Christians

who died at the hands of pagan persecutors can have been at

most only a tiny fraction of the number who later died at the

hands of their fellow Christians. From the reign of the first

Christian emperor onwards, Christians were persecuted far more

savagely by other Christians than they were by anyone else.

|

The Myth of Persecution, by Candida

Moss, professor of New Testament and Early Christianity

at the University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana in

the USA was published by Harper Collins in 2013 (ISBN

978-0-06-210452-6 )

Professor Moss demonstrates that the "Age of Martyrdom",

when Christians suffered persecution from the Roman authorities

and lived in fear of being thrown to the lions, is fictional.

There was never sustained, targeted persecution of Christians

by Imperial Roman authorities. Most stories of individual

martyrs are pure invention, and even the oldest and most

historically accurate stories of martyrs and their sufferings

have been altered and re-written by later editors, so

that it is impossible to know for sure what any of the

martyrs actually thought, did or said, or what happened

to them.

|

|

|

We still hear occasional stories of how Christians are viciously

persecuted for their beliefs. Such stories were told of the

treatment of Christians in the USSR before the thawing of relations

between East and West in the late 1980s. Strangely, they lost

their appeal when Soviet communism crumbled and it became possible

to investigate the allegations. A good example was provided

by Vasily Shipilov, a Christian Priest who had been imprisoned

in the Soviet Union for his religious convictions. The Reverend

Dick Rogers had led an international campaign for the release

of this persecuted Christian hero. In 1988 Shipilov was released.

When he visited Britain he turned out to have been imprisoned

not for his religious beliefs but for vagrancy. He was not a

priest and was uncertain whether he had ever been baptised31.

We also discovered that the Orthodox hierarchy, far from being

persecuted by the communists, had been working with them and

had been paid money for their extensive cooperation. If religious

propaganda can distort contemporary truth so wildly, one must

wonder how much it might have done over two millennia.

We now look at the other side of the coin and review a few

of the principal groups that have been persecuted by Christians.

Here the evidence of heavy and sustained persecution is stronger:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buy the Book from Amazon.co.uk

|

|

|

| |

| |

| More Books |

|

|

|