| |

|

|

There is no greater hatred in the

world than hatred of ignorance for knowledge.

|

|

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

|

The

ancient Greeks were outstanding mathematicians, philosophers

and scientists. One of them, Empedocles, showed that air is

a material substance and not just a void, experimented with

centrifugal force, knew about sex in plants, proposed a theory

of evolution, speculated that light travels at a finite speed,

and was aware that solar eclipses are caused by alignments of

the Sun, Moon and Earth. Knowledge of astronomy was advanced.

Hipparchus accurately determined the distance between Earth

and the Moon1

, estimated the length of the lunar month to within a second,

and discovered the precession of the equinoxes. Some of the

achievements of the ancient Greeks are astonishing. Heron of

Alexandria invented an internal combustion engine. Thales of

Miletus, who lived around six centuries before the birth of

Jesus, was familiar with static electricity. By Roman times

elementary batteries had been invented, although no uses for

them appear to have been exploited. Foundations of many modern

sciences were laid by the Greeks from astronomy to botany, and

even specialised fields of physics such as optics, hydrostatics,

pneumatics, and mechanics. Modern mathematics is full of references

to pioneering Greek mathematicians: Euclidean planes, Diophantine

equations, the theory of Pappus, and so on. The

ancient Greeks were outstanding mathematicians, philosophers

and scientists. One of them, Empedocles, showed that air is

a material substance and not just a void, experimented with

centrifugal force, knew about sex in plants, proposed a theory

of evolution, speculated that light travels at a finite speed,

and was aware that solar eclipses are caused by alignments of

the Sun, Moon and Earth. Knowledge of astronomy was advanced.

Hipparchus accurately determined the distance between Earth

and the Moon1

, estimated the length of the lunar month to within a second,

and discovered the precession of the equinoxes. Some of the

achievements of the ancient Greeks are astonishing. Heron of

Alexandria invented an internal combustion engine. Thales of

Miletus, who lived around six centuries before the birth of

Jesus, was familiar with static electricity. By Roman times

elementary batteries had been invented, although no uses for

them appear to have been exploited. Foundations of many modern

sciences were laid by the Greeks from astronomy to botany, and

even specialised fields of physics such as optics, hydrostatics,

pneumatics, and mechanics. Modern mathematics is full of references

to pioneering Greek mathematicians: Euclidean planes, Diophantine

equations, the theory of Pappus, and so on.

The outlook of Christians was fundamentally different from

that of the ancient Greeks. According to Christians, God revealed

himself through the Bible and the Church. As Tertullian

explained, scientific research [inquisitio] became superfluous

once the gospel of Jesus Christ was available:

We have no need of curiosity after Jesus Christ, nor of research

after the gospel. When we believe, we desire to believe nothing

more. For we believe that there is nothing else that we need

to believe.

De praescnptione haereticorum (On the Rule of the Heretic)

The

Church taught that it knew all there was to be known. Christian

knowledge was comprehensive and unquestionable. Rational investigation

was therefore unnecessary. Existing learning was not merely

superfluous, but positively harmful. Theologians were convinced

that God had defined strict limits on the knowledge that human

beings might acquire, and anything else was "sorcery".

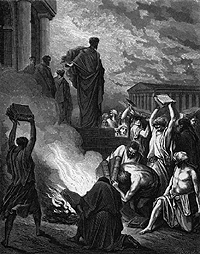

When Saint Paul visited the great city of Ephesus many Christians

burned their books (or scrolls) because they were considered

to contain sorcery. This set the tone for Christian thought

for centuries. In the fourth century Eusebius attacked scientific

enquiry, dismissing it as "useless labour". St.

Augustine of Hippo who regarded scientific enquiry as a

worse sin than lust, also said that "Hell was made for

the inquisitive". To seek to discover more was a sin and

therefore also a crime, the crime of curiositas2

. For him, scientific curiosity ("knowledge and learning")

was as a more serious sin than lust: The

Church taught that it knew all there was to be known. Christian

knowledge was comprehensive and unquestionable. Rational investigation

was therefore unnecessary. Existing learning was not merely

superfluous, but positively harmful. Theologians were convinced

that God had defined strict limits on the knowledge that human

beings might acquire, and anything else was "sorcery".

When Saint Paul visited the great city of Ephesus many Christians

burned their books (or scrolls) because they were considered

to contain sorcery. This set the tone for Christian thought

for centuries. In the fourth century Eusebius attacked scientific

enquiry, dismissing it as "useless labour". St.

Augustine of Hippo who regarded scientific enquiry as a

worse sin than lust, also said that "Hell was made for

the inquisitive". To seek to discover more was a sin and

therefore also a crime, the crime of curiositas2

. For him, scientific curiosity ("knowledge and learning")

was as a more serious sin than lust:

To this the sin [of lust] is added another form of temptation

more manifoldly dangerous. For besides that concupiscence

of the flesh which consisteth in the delight of all senses

and pleasures, wherein its slaves, who go far from Thee, waste

and perish, the soul hath, through the same senses of the

body, a certain vain and curious desire, veiled under the

title of knowledge and learning, not of delighting in the

flesh, but of making experiments through the flesh.2a

The Christian comitment to obedience rather than knowledge

meant that what you saw as white was black if the Church said

it was. Church dogma thus over-rode all empiricle evidence into

modern times.

To be right in everything, we ought always to hold that the

white which I see, is black, if the Hierarchical Church so

decides it

(St. Ignatius Loyola, 1491 - 1556, Spiritual Exercises, Thirteenth

Rule.)

Christianity brought the Dark Ages to Europe, a period when

scientific endeavour was abandoned and learning of all kinds

was rooted out and destroyed. With the exception of military

technology, the Church was to oppose advances in virtually every

scientific discipline for many hundreds of years. Philosophers

were persecuted and their books burned. Such was the persecution

that men of learning were driven to destroy their own libraries

rather than risk a volume being seen by a Christian informer.

Efforts were made to destroy evidence of Greek successes. We

can never know how much was lost forever. Some Greek learning

was preserved because Christian heretics, notably Nestorians,

took it east with them when they fled the wrath of the orthodox

Church. These refugees flourished under Zoroastrian and Muslim

rulers in centres like Damascus, Cairo, Baghdad and Gondeshapur

in Persia. There they translated surviving works into Syriac,

Hebrew and Arabic.

It was later re-translations of these works, mainly from Arabic

into Latin, that fuelled humanism and the development of the

scientific method in western Europe almost a millennium after

Christian orthodoxy had begun its intellectual holocaust. Conquests

of Constantinople by crusaders in 1204 and then by the Turks

in 1453 both resulted in the flight of Greek scholars to western

Europe. They brought remnants of more ancient works that had

been preserved in the East. These influxes encouraged the revival

of Greek learning, leading to an intellectual rebirth that we

know as the European Renaissance.

Having produced no distinctive philosophy of its own, the

early Church had adopted the philosophical ideas of Plato. For

centuries Plato was honoured as a sort of quasi-Christian. Among

the works brought back from the East were the writings of his

pupil Aristotle. Aristotle appealed to medieval Christians even

more than Plato, but some of his ideas seemed incompatible with

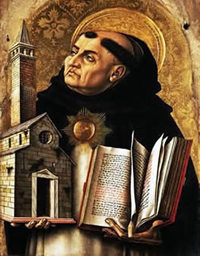

theirs. Thomas Aquinas attempted to reconcile Aristotelian thought

with Christianity, and for a while it was accepted that he had

succeeded. Aristotle was now credited with almost divine authority,

and it became as difficult to overturn his ideas as it was biblical

ones. Time after time the Church would seek to suppress scientific

discoveries by reference either to the Bible or to Aristotle.

Ignatius Loyola summed up the traditional Christian view when

he said “We sacrifice the intellect to God” and

Martin Luther was even more direct in expressing the view that

“Reason is the Devil's harlot”. At the end of the

seventeenth century churchmen — even Anglican churchmen

— were still claiming that the Christian religion was the

only real source of knowledge 3

, and the Bible was still regarded an infallible and comprehensive

encyclopædia. It provided information on the origins,

history and nature of the Universe, Earth, animals and mankind.

How such ideas came to be abandoned by most Christians is the

history of Western science.

We will now look at examples of what happened when new scientific

truths contradicted old religious ones, beginning with the most

famous case of all.

I know that I am mortal by nature, and ephemeral; but when

I trace at my pleasure the windings to and fro of the heavenly

bodies I no longer touch the earth with my feet: I stand in

the presence of Zeus himself and take my fill of ambrosia.

Ptolemy, Almagest

For religious reasons it was necessary

for Christian scholars to place Earth at the centre of all creation.

God had created the Universe for humans, so it was natural that

he should build it around them. Accepted Church doctrine in

early times was that our world was flat and circular, and sat

immobile at the centre of the cosmos4.

The vault of the sky was a solid structure, a huge dome rather

like a gigantic planetarium. Stars were physically moved around

its inner surface by angels. Anyone adventurous and blasphemous

enough could conceivably break through the firmament at the

edge of the world into the hidden heavenly realms beyond.

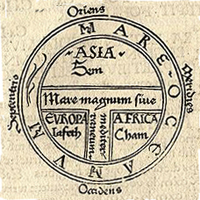

| |

|

In later medieval thought the earth was

a disk - flat and round - so it was theoretically possible

to find the edge of the world and break through to the

first heaven.

|

|

|

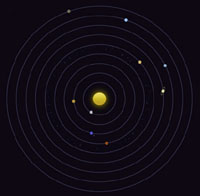

Within

the dome theologians imagined a number of concentric hemispheres

separating a series of holy regions — the seven heavens

that appear in Jewish, Christian and Muslim literature 5.

Churchmen knew exactly where the centre of their circumscribed

world was. It was Jerusalem, as medieval maps confirm. Indeed

the precise spot within Jerusalem could be identified, for it

was where Jesus had been crucified. It is supposedly located

in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The site of the crucifixion

thus marked the radial centre of of a disc, below the hemispherical

firmament — the exact centre of the Universe. Within

the dome theologians imagined a number of concentric hemispheres

separating a series of holy regions — the seven heavens

that appear in Jewish, Christian and Muslim literature 5.

Churchmen knew exactly where the centre of their circumscribed

world was. It was Jerusalem, as medieval maps confirm. Indeed

the precise spot within Jerusalem could be identified, for it

was where Jesus had been crucified. It is supposedly located

in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The site of the crucifixion

thus marked the radial centre of of a disc, below the hemispherical

firmament — the exact centre of the Universe.

Anyone

who queried church teachings, or even carried out proto-scientific

investigations was liable to severe penalties, especially once

the Inquisition had been created to root out heresy. Often we

do not know the supposed nature of the heresy - in at least

some cases it might have been revealing that the earth is not

flat. All we know for certain is that proto-scientists were

tried and convicted for the crime of heresy - ie the crime of

disagreeing with the Church. Anyone

who queried church teachings, or even carried out proto-scientific

investigations was liable to severe penalties, especially once

the Inquisition had been created to root out heresy. Often we

do not know the supposed nature of the heresy - in at least

some cases it might have been revealing that the earth is not

flat. All we know for certain is that proto-scientists were

tried and convicted for the crime of heresy - ie the crime of

disagreeing with the Church.

Pietro d'Abano (aka Petrus De Apono or Aponensis) was an Italian

astronomer, philosopher, and professor of medicine in Padua.

He was called before the inquisition but died in their prison

in 1315 before the end of his trial. He was nevertheless convicted

of heresy and his body ordered to be burned. When his body was

found to have been removed and hidden, the Inquisition had to

be content with burning his effigy.

Cecco

d'Ascoli (AKA Francesco degli Stabili), was another famous Italian

polymath – an astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, mineralogist,

encyclopaedist, physician and poet, and victim of the Inquisition.

Since Pietro d'Abano had died in prison, Cecco holds the distinction

of being the first university scholar to be killed by the Inquisition

for heresy. Cecco

d'Ascoli (AKA Francesco degli Stabili), was another famous Italian

polymath – an astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, mineralogist,

encyclopaedist, physician and poet, and victim of the Inquisition.

Since Pietro d'Abano had died in prison, Cecco holds the distinction

of being the first university scholar to be killed by the Inquisition

for heresy.

Inquisitors supposedly accused him of casting Jesus' horoscope,

though his real crime might have been to say that the earth

was spherical. He was burned at Florence on 26 September 1327,

the day after he was sentences, in his seventieth year.

|

Cecco d'Ascoli, Professor of astrology

at the University of Bologna (left),

was represented as having made a pact with the Devil

|

|

|

Respectable

churchmen continued to endorse flat earth theories, arguing

against a spherical earth. Zacharia Lilio, a canon of the Basilica

of St. John Lateran in Rome wrote Contra Antipodes in

1496 (after Columbus) stating explicitly that "That the

earth is not round". Respectable

churchmen continued to endorse flat earth theories, arguing

against a spherical earth. Zacharia Lilio, a canon of the Basilica

of St. John Lateran in Rome wrote Contra Antipodes in

1496 (after Columbus) stating explicitly that "That the

earth is not round".

Later theologians accepted that the heavens were fully spherical

and rotated about a stationary spherical Earth suspended in

space. These heavens were made of transparent crystal, which

explained why they could not be seen. The Earth lay at divine

rest at the centre of all creation, just as God lay at divine

rest in his heaven

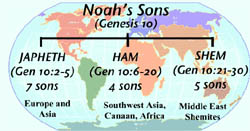

This

second spherical theory was certainly an advance on what had

been believed before, but it was still well behind the ancient

Greeks, who had known that Earth is spherical almost 2,000 years

earlier. Parmenides of Elea recognised it to be so in the fifth

century BC. Pythagoreans found proof that Earth was round: they

noted that our planet cast a curved shadow on the surface of

the Moon during lunar eclipses. Other Greeks spoke of the opposite

side of the world where the Sun shone while it was their night.

Eratosthenes of Alexandria (275-194 BC) calculated Earth's size

and arrived at a circumference of 252,000 stades, which is thought

to correspond to 39,690 km (24,663 miles) — only a little

short of the correct figure for the polar circumference, which

is 40,008 km (24,860 miles). Eratosthenes also developed the

system of latitude and longitude. That Earth was spherical was

so well established by Roman times that emperors carried an

orb to signify their sovereignty over the whole world. This

second spherical theory was certainly an advance on what had

been believed before, but it was still well behind the ancient

Greeks, who had known that Earth is spherical almost 2,000 years

earlier. Parmenides of Elea recognised it to be so in the fifth

century BC. Pythagoreans found proof that Earth was round: they

noted that our planet cast a curved shadow on the surface of

the Moon during lunar eclipses. Other Greeks spoke of the opposite

side of the world where the Sun shone while it was their night.

Eratosthenes of Alexandria (275-194 BC) calculated Earth's size

and arrived at a circumference of 252,000 stades, which is thought

to correspond to 39,690 km (24,663 miles) — only a little

short of the correct figure for the polar circumference, which

is 40,008 km (24,860 miles). Eratosthenes also developed the

system of latitude and longitude. That Earth was spherical was

so well established by Roman times that emperors carried an

orb to signify their sovereignty over the whole world.

In

the sixth century BC, Thales of Miletus learned from the Babylonians

how to predict the motion of heavenly bodies. He was able to

anticipate a solar eclipse in 585 BC. Anaxagoras of Clazomenœ,

who was born around 500 BC, held the Sun to be an incandescent

mass of hot stone — as near to the truth as he could have

got. He also said that the Moon shone merely because of the

Sun's reflected light, as indeed it does. Pythagoras seems to

have speculated in the sixth century BC that Earth went round

the Sun, not the Sun round Earth. Aristotle mentions Pythagoreans

who regarded Earth as a planet — a heavenly body circling

around the Sun, the central fire that created night and day.

Towards the middle of the third century BC, Aristarchus of Samos

further developed the Pythagorean theory that Earth was in motion

about the Sun. Other philosophers wondered why, if the Pythagorean

theory were right, the fixed stars did not appear to change

position as Earth moved. But Aristarchus had an explanation

for this absence of parallax. He pointed out that it could be

accounted for by the vast distances to the fixed stars, a theory

that was to be vindicated in the nineteenth century. In

the sixth century BC, Thales of Miletus learned from the Babylonians

how to predict the motion of heavenly bodies. He was able to

anticipate a solar eclipse in 585 BC. Anaxagoras of Clazomenœ,

who was born around 500 BC, held the Sun to be an incandescent

mass of hot stone — as near to the truth as he could have

got. He also said that the Moon shone merely because of the

Sun's reflected light, as indeed it does. Pythagoras seems to

have speculated in the sixth century BC that Earth went round

the Sun, not the Sun round Earth. Aristotle mentions Pythagoreans

who regarded Earth as a planet — a heavenly body circling

around the Sun, the central fire that created night and day.

Towards the middle of the third century BC, Aristarchus of Samos

further developed the Pythagorean theory that Earth was in motion

about the Sun. Other philosophers wondered why, if the Pythagorean

theory were right, the fixed stars did not appear to change

position as Earth moved. But Aristarchus had an explanation

for this absence of parallax. He pointed out that it could be

accounted for by the vast distances to the fixed stars, a theory

that was to be vindicated in the nineteenth century.

Ancient Greeks had written about people living on the other

side of the world, in an unknown land, the antipodes. In the

eighth century, Vergilius of Salzburg revived the idea that

the earth was spherical and on the other side of the earth people

might be found living in the Antipodes. Saint Boniface condemned

the idea as "iniquitous and perverse" and "contrary

to the scriptures". The then Pope, Zozimus, regarded the

idea as heretical6

but as this heresy occurred before the founding of the Inquisition,

Vergilius suffered no long term problems for voicing his opinion

because of lack of evidence - if evidence had been available

the Pope would have authorised a council to try and punish him.

The

ancient Pythagorean view was revived by Nicolaus Copernicus

early in the sixteenth century, over 2,000 years after it had

first been put forward. Copernicus did not dare to publish his

ideas on the matter, because the Church was certain that Earth

lay at the centre of everything. He kept his book, De Revolutionibus

Orbium Cœlestium, secret for 36 years. It was published

only after his death. The Inquisition would later condemn his

cosmology as "that false Pythagorean doctrine utterly contrary

to the Holy Scriptures". Their scriptural prooftext included

Ecclesiastes 1:5, which talks about the Sun rising and setting,

and Psalm 104:5 which says that Earth can never be moved. The

Church knew beyond all doubt that the Sun rotated about Earth

because on one occasion God had made it stand still in the sky

(Joshua 10:12-13). According to the greatest Church authorities

it was not possible to believe in the Pythagorean/Copernican

system and still remain a Christian. Even Martin Luther agreed

that this cosmology was incompatible with Christian faith. Here

he is ("Works," Volume 22, c. 1543) referring to Copernicus

and his theory: The

ancient Pythagorean view was revived by Nicolaus Copernicus

early in the sixteenth century, over 2,000 years after it had

first been put forward. Copernicus did not dare to publish his

ideas on the matter, because the Church was certain that Earth

lay at the centre of everything. He kept his book, De Revolutionibus

Orbium Cœlestium, secret for 36 years. It was published

only after his death. The Inquisition would later condemn his

cosmology as "that false Pythagorean doctrine utterly contrary

to the Holy Scriptures". Their scriptural prooftext included

Ecclesiastes 1:5, which talks about the Sun rising and setting,

and Psalm 104:5 which says that Earth can never be moved. The

Church knew beyond all doubt that the Sun rotated about Earth

because on one occasion God had made it stand still in the sky

(Joshua 10:12-13). According to the greatest Church authorities

it was not possible to believe in the Pythagorean/Copernican

system and still remain a Christian. Even Martin Luther agreed

that this cosmology was incompatible with Christian faith. Here

he is ("Works," Volume 22, c. 1543) referring to Copernicus

and his theory:

People give ear to an upstart astrologer who strove to show

that the earth revolves, not the heavens or the firmament,

the sun and the moon. Whoever wishes to appear clever must

devise some new system, which of all systems is of course

the very best. This fool wishes to reverse the entire science

of astronomy; but sacred Scripture tells us that Joshua commanded

the sun to stand still, and not the earth.

The

Catholic Church taught that sin and imperfection existed only

at the centre of the Universe — on Earth and as far above

its surface as the Moon. God's abode, the heavens, beyond the

lunar orbit, were perfect. On Earth were imperfection and decay,

and natural motion was in a straight line; in Heaven was perfection

and constancy, and natural motion was perfectly circular. All

celestial orbits were thus circular, and in particular the Sun

moved around Earth in a circle. Apart from being wrong about

which body revolves around which, the Church was also mistaken

about the shape of celestial orbits. If heavenly bodies revolved

around Earth in circular orbits then they would have constant

apparent brightnesses. But the apparent brightnesses of planets

vary, an observation that had led ancient Greeks to deduce,

correctly, that the distances between Earth and various other

planets were not constant. In fact, Earth and the other planets

all orbit the Sun, and their orbits do not have the shapes of

circles but rather ellipses, albeit ellipses that (for Earth

and most of the other planets) closely resemble circles. In

an impressive piece of mathematics, the German astronomer Johannes

Kepler calculated the laws of motion for the elliptical orbits

of the planets around the Sun. His book The New Astronomy

effectively proved Copernicus' heliocentric theory. It was placed

on the Index in 1609. The

Catholic Church taught that sin and imperfection existed only

at the centre of the Universe — on Earth and as far above

its surface as the Moon. God's abode, the heavens, beyond the

lunar orbit, were perfect. On Earth were imperfection and decay,

and natural motion was in a straight line; in Heaven was perfection

and constancy, and natural motion was perfectly circular. All

celestial orbits were thus circular, and in particular the Sun

moved around Earth in a circle. Apart from being wrong about

which body revolves around which, the Church was also mistaken

about the shape of celestial orbits. If heavenly bodies revolved

around Earth in circular orbits then they would have constant

apparent brightnesses. But the apparent brightnesses of planets

vary, an observation that had led ancient Greeks to deduce,

correctly, that the distances between Earth and various other

planets were not constant. In fact, Earth and the other planets

all orbit the Sun, and their orbits do not have the shapes of

circles but rather ellipses, albeit ellipses that (for Earth

and most of the other planets) closely resemble circles. In

an impressive piece of mathematics, the German astronomer Johannes

Kepler calculated the laws of motion for the elliptical orbits

of the planets around the Sun. His book The New Astronomy

effectively proved Copernicus' heliocentric theory. It was placed

on the Index in 1609.

|

Detail from MS. Canon. Ital. 258 folio

006v.

Concentric rings Earth, Water, Air, and Fire, followed

by

the orbits of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars,

Jupiter and Saturn.

|

|

|

Another error of the Church was its denial that Earth spins

on its own axis. Heraclides of Pontus had realised in the fourth

century BC that Earth rotates once every 24 hours. A little

later Aristarchus of Samos (c.310-230) had advanced a complete

Copernican hypothesis. He said that all planets including Earth

orbit the Sun, and that Earth itself rotates on its axis. By

the early 1600s, Copernicus and Kepler had vindicated Aristarchus,

but the Roman Church could not accept that he had been right,

much less that it had been wrong.

The

greatest scientist of his day, Galileo Galilei, was fascinated

by the evidence, and saw that the model proposed by Aristarchus

and Copernicus was better than the one taught by the Church.

Galileo was censured for teaching Copernican cosmology in 1616.

Suddenly, the full implications of this cosmology were appreciated.

Copernicus was posthumously declared a heretic and his cosmological

treatise placed on the Index. The

greatest scientist of his day, Galileo Galilei, was fascinated

by the evidence, and saw that the model proposed by Aristarchus

and Copernicus was better than the one taught by the Church.

Galileo was censured for teaching Copernican cosmology in 1616.

Suddenly, the full implications of this cosmology were appreciated.

Copernicus was posthumously declared a heretic and his cosmological

treatise placed on the Index.

Galileo could no longer teach the theory, but with papal approval

he continued to discuss it. His discussions did not favour the

Church's theory, so he found himself in trouble again. In 1633

Pope Urban VIII had him arraigned on a charge of heresy. He

was found guilty, a predicable verdict since, in line with established

Inquisition practice, he was not allowed to mount a defence.

…I humbly begged His Holiness to agree to give him

the opportunity to justify himself. Then His Holiness answered

that in these matters of the Holy Office the procedure was

simply to arrive at a censure and then call the defendant

to recant.

Letter from Francesco Niccolini to Andrea Cioli, about Galileo,

dated 5th September 1632

His sentence contained the following statements:

…by order of His Holiness and Most Eminent and Most

Reverend Lord Cardinals of this Supreme and Universal Inquisition,

the Assessor Theologians assessed the two propositions of

the Sun's stability and the earth's motion as follows:

That the Sun is the centre of the universe and motionless

is a proposition which is philosophically absurd and false,

and formally heretical, for being explicitly contrary to Holy

Scripture;

That the earth is neither the centre of the universe nor

motionless but moves even with diurnal rotation is philosophically

equally absurd and false, and theologically at least erroneous

in the Faith 7.

Galileo

recanted under threats of torture by the Inquisition. He was

obliged to say that it was the Sun and not Earth that moved,

and to abjure his heretical depravity in claiming otherwise.

He may have been tortured — we would not know because victims

of the Inquisition were obliged to take an oath not to divulge

what had happened to them. In any case he would have before

his mind the image of Giordano Bruno, another great thinker

of the age. Bruno had also considered possibilities denied by

the Church. He said that stars were really distant suns, and

that there could be inhabited planets orbiting them. He rejected

the idea of a solid firmament. He thought the Universe infinite

and denied that Earth was at its centre 8.

In 1600 he had been publicly burned at the stake in Rome for

his heresies. Galileo

recanted under threats of torture by the Inquisition. He was

obliged to say that it was the Sun and not Earth that moved,

and to abjure his heretical depravity in claiming otherwise.

He may have been tortured — we would not know because victims

of the Inquisition were obliged to take an oath not to divulge

what had happened to them. In any case he would have before

his mind the image of Giordano Bruno, another great thinker

of the age. Bruno had also considered possibilities denied by

the Church. He said that stars were really distant suns, and

that there could be inhabited planets orbiting them. He rejected

the idea of a solid firmament. He thought the Universe infinite

and denied that Earth was at its centre 8.

In 1600 he had been publicly burned at the stake in Rome for

his heresies.

Old and sick, and well aware of Bruno's fate, Galileo now knelt

in penitence before the inquisitors. His writing on the subject,

the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,

was placed on the Index. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

In fact he spent the rest of his life under house arrest, a

mercy almost certainly attributable to the fact that he was

a personal friend of the reigning Pope.

Galileo's

Copernican ideas had not been the first to create difficulties.

He had made many scientific discoveries, a number of which had

contradicted Church teachings. He had looked through his early

telescope at the Moon and realised that it was not at all like

the theologians said. It had mountains, just as the Greek philosopher

Anaxagoras had said 2,000 years earlier (anyone with normal

eyesight and an open mind can see their shadows), and these

mountains were interspersed with plains. Few theologians would

look through his telescope to confirm his findings, for they

already knew for a fact that the Moon had a smooth polished

surface. Those who did look said that the shadows they saw must

be blemishes in the telescope lenses. They did not test this

hypothesis by rotating the telescope, or by using another telescope.

There was no point — again because they knew for a fact

that the surface was smooth. Galileo's

Copernican ideas had not been the first to create difficulties.

He had made many scientific discoveries, a number of which had

contradicted Church teachings. He had looked through his early

telescope at the Moon and realised that it was not at all like

the theologians said. It had mountains, just as the Greek philosopher

Anaxagoras had said 2,000 years earlier (anyone with normal

eyesight and an open mind can see their shadows), and these

mountains were interspersed with plains. Few theologians would

look through his telescope to confirm his findings, for they

already knew for a fact that the Moon had a smooth polished

surface. Those who did look said that the shadows they saw must

be blemishes in the telescope lenses. They did not test this

hypothesis by rotating the telescope, or by using another telescope.

There was no point — again because they knew for a fact

that the surface was smooth.

Galileo found other difficulties with Church orthodoxy. Following

Aristotle, the Church taught that natural motion on Earth was

always in a straight line, but Galileo showed that projectiles

describe parabolic curves. Aristotle said that a heavy object

will naturally fall to the ground faster than a light one. Galileo

showed that all objects fall at identical rates under gravity

(unless some other force, like air resistance, acts on them).

Since the Church had adopted Aristotle's teaching as its own,

it was wrong every time he was.

The

Church also disputed the existence of the moons of Jupiter.

With his telescope Galileo had seen four moons in 1610, but

churchmen said they did not exist. They could not exist because

all heavenly bodies rotated around Earth. The existence of sunspots

was another inconvenience. These were first studied seriously

from around 1610 by Galileo and a German Jesuit priest, Christoph

Scheiner (among others). Scheiner had to publish his findings

under a pseudonym, because of Church opposition. The familiar

argument was that the Sun, being a heavenly creation of God,

must be perfect. Therefore its face could not suffer any form

of blemish. The existence of sunspots thus continued to be disputed

by theologians long after their discovery, even though they

could (and can) sometimes be clearly seen with the naked eye

around sunset. Comets provided yet another difficulty. On the

one hand they were recognised as destructible, which meant that

they must exist within the imperfect region bounded by the Moon;

on the other hand it was realised in the seventeenth century

that they orbit the Sun — which meant that they must lie

beyond the Moon's orbit. Once again theological cosmology contradicted

scientific cosmology. Whether they existed within or without

the lunar orbit, the Church deemed that comets must have a purpose,

and that purpose could only be to act as divine portents. Theologians

explained how angels created them as the need arose and dismantled

them when they were no longer needed 9. The

Church also disputed the existence of the moons of Jupiter.

With his telescope Galileo had seen four moons in 1610, but

churchmen said they did not exist. They could not exist because

all heavenly bodies rotated around Earth. The existence of sunspots

was another inconvenience. These were first studied seriously

from around 1610 by Galileo and a German Jesuit priest, Christoph

Scheiner (among others). Scheiner had to publish his findings

under a pseudonym, because of Church opposition. The familiar

argument was that the Sun, being a heavenly creation of God,

must be perfect. Therefore its face could not suffer any form

of blemish. The existence of sunspots thus continued to be disputed

by theologians long after their discovery, even though they

could (and can) sometimes be clearly seen with the naked eye

around sunset. Comets provided yet another difficulty. On the

one hand they were recognised as destructible, which meant that

they must exist within the imperfect region bounded by the Moon;

on the other hand it was realised in the seventeenth century

that they orbit the Sun — which meant that they must lie

beyond the Moon's orbit. Once again theological cosmology contradicted

scientific cosmology. Whether they existed within or without

the lunar orbit, the Church deemed that comets must have a purpose,

and that purpose could only be to act as divine portents. Theologians

explained how angels created them as the need arose and dismantled

them when they were no longer needed 9.

There was more. When Galileo turned his telescope on Venus

he noticed that it had phases like the Moon. These phases had

been predicted by the heliocentric theory, and provided another

problem for the Church. Yet another difficulty was that through

his telescope Galileo could see thousands of stars that were

too dim to be seen with the naked eye. The problem here was

that the Church taught that the stars, like everything else,

existed only for the benefit of mankind. To devout churchmen

it did not make sense for God to place anything in the firmament

unless it visibly shed light, or was of some other practical

use to people on Earth.

For similar reasons the Church stayed in the age of astrology

while people were pioneering modern astronomy. Theologians knew

for certain that devils were given to molesting people at certain

phases of the Moon 10.

Even popes used the services of astrologers. For example, Julius

II chose the date of his coronation on astrological calculations,

and Paul III chose the time of each consistory (meeting of the

college of cardinals) on a similar basis 11.

Leo X founded a chair of astrology. Astrology might be useful,

but astronomy was not, because the Church already knew everything

to be known about the mechanics of the Universe from God's infallible

handbook. Even the men who pioneered astronomy spent their time

trying to reconcile Church teachings to the real world. The

consequence was that great minds were held back by fruitless

attempts to match theology and observation. Scholars tried to

explain planetary orbits as epicycles (i.e. compound circular

motions) for a long time, because circles would be less offensive

to orthodox religious ideas.

|

The rings of Saturn presented yet another

problem when they were first seen through a telescope

as they could not be easily explained by theologians.

As it was held that all parts of Jesus Christ were in

heaven, including his prepuce, theologians put two and

two together. Leo Allatius (1586 – 1669, a theologian

and keeper of the Vatican library contended that the heavenly

foreskin formed the rings of Saturn in his work Die

Praeputio Domine Nosri Jesu Christi Diatriba, (A

Discussion of the Foreskin of Our Lord Jesus Christ)

|

|

|

Galileo himself spent time trying to accommodate the biblical

account of the Sun standing still. Kepler might have made further

important discoveries if he had not been constrained by the

belief that planets are guided by angels. So might later cosmologists

if they had not required God to wind up their mechanical universe

like a giant clockwork toy. Such ideas affected even Isaac Newton.

By the 1680s, Newton had deduced the same results concerning

planetary motion as Kepler had arrived at, using his new theory

of gravitation. He still imagined God nudging the planets back

into line from time to time, which invited a degree of teasing

from Leibnitz who wondered why God failed to get it right first

time. Despite this, Newton's theory marked a turning point.

Even if it was conceded that supernatural forces were needed

for occasional fine-tuning, theologians were horrified by the

idea of forces that acted without physical contact. If gravity

could explain basic planetary motions, then supernatural explanations

might soon become superfluous altogether — those guiding

angels would become redundant. Newton was criticised for presuming

to intrude into forbidden territory. As Edmund Halley put it,

Newton had penetrated the secret mansions of the gods. Churchmen

had imagined that they held all the keys to God's heavenly mansions

and did not like trespassers, especially trespassers like Newton

who could open doors that remained closed to them.

Edmund Halley is best remembered for giving his surname to

a famous comet. He realised that various comets recorded in

history were in fact the same comet reappearing every 76 years.

This undermined the idea that comets were divine portents. It

also suggested that theologians had been wrong about angels

constructing and dismantling them as the need arose. The Anglican

Church did not like trespassers any more than the Roman Catholic

Church did, especially if their religious views were less than

orthodox. Halley's views were less than orthodox. He believed

that the world would continue forever, an idea that contradicted

the doctrine of the Second Coming of Christ. Halley was suspected

of atheism, and because of this he failed to win the Savilian

Chair of Astronomy at Oxford in 1691-2. Its gift lay with the

Anglican Church. Halley's was a petty affair in comparison to

Galileo's , but the principle was the same. Churches did not

want to hear theories that contradicted their own, and they

did not want other people to hear them either.

Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

stayed on the Index until 1835, an annually increasing embarrassment

for educated Roman Catholic believers. By that time the divine

role had been reduced to nothing. The French mathematician Pierre-Simon

Laplace had established that those oddities that Newton had

identified in the planetary orbits did not after all require

gods or angels to correct them. They were, he showed, self-correcting.

When Napoleon asked him where God came into celestial mechanics,

Laplace replied "I have no need for that hypothesis".

Laplace also noted that of all cosmologists Aristarchus had

had the most accurate ideas of the grandeur of the universe.

The reason we see no parallax in the distant stars is their

great distance - which meant that the Earth is but a tiny speck

in a vast universe. Aristarchus and Bruno were both vindicated.

The cosy little universe which consisted of the earth and the

crystal spheres around it was gone for ever. In Medieval times

the words for "universe" and "world" had

been interchangeable - now the Church-approved Medieval model

would be no more than a quaint memory. It was now clear to many

that the theologians and their infallible truths had been comprehensively

wrong. There is no solid firmament. Earth is not at the centre

of the Universe, and nor is it stationary. Neither the Sun nor

the planets revolve around it. Celestial orbits are not circular,

and neither in general is motion in Earth's gravitational field

a straight line. The Moon is not a perfect silver disk, nor

is the Sun a perfect gold one. We live on one insignificant

planet in a vast universe.

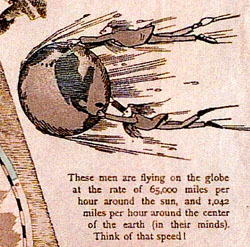

|

Flat Earth map drawn by Orlando Ferguson

in 1893. The map features "Four Angels standing on

the Four Corners of the Earth" —Rev. 7: 1, a

note that there are "Four Hundred Passages in the

Bible that Condemn the Globe Theory, or the Flying Earth,

and None Sustain It." and also pokes fun at people

who accept the scientific rather than the biblical theory.

|

|

|

Even so in the nineteenth century there were still plenty of

Christians to who refused to accept the truth, and still adhered

to the flat earth theory. Some, like the Christian minister

Wilbur Glenn Voliva who lived well into the twentieth century,

became multi-millionaires from vast numbers of like-minded followers.

I believe this Earth is a stationary plane; that it rests

upon water; and that there is no such thing as the Earth moving,

no such thing as the Earth's axis or the Earth's orbit. It

is a lot of silly rot, born in the egotistical brains of infidels.

(Wilbur Glenn Voliva (1870 – 1942))

There are still a few Christian flat earthers today, along

with millions of Moslem flat-earthers. The Moslems quote the

infallible Koran, and the Christians the infallible bible. At

the same time, many modern Christian apologists have tried to

deny that the Church ever taught that the world was flat. 12.

|

Traditional Christian prooftexts from

the bible, proving the earth to be flat,

cited by Orlando Ferguson:

|

- And his hands were steady until the going down of

the sun—Ex. 17: 12.

- And the sun stood still, and the moon stayed.—Joshua

10: 12–13.

- The world also shall be stable that it not be moved.—Chron.

16: 30.

- To him that stretched out the earth, and made great

lights (not worlds).—Ps. 136: 6–7.

- The sun shall be darkened in his going forth.—Isaiah

12: 10.

- The four corners of the Earth.—Isaiah 11: 12.

- The whole earth is at rest.—Isaiah 14: 7.

- A prophecy concerning the globe theory.—Isaiah:

29th chapter.

- So the sun returned ten degrees.—Isaiah 38: 8–9.

- It is he that sitteth upon the circle of the earth.—Isaiah

40: 22.

- He that spreads forth the earth.—Isaiah 52: 5.

- That spreadeth abroad the earth by myself.—Isaiah

54: 24.

- My hand also hath laid the foundation of the earth.—Isaiah

58: 13.

- Thus sayeth the Lord, which giveth the sun for a light

by day, and the moon and stars for a light by night

(not worlds).—Jer. 31: 35–36.

- The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon

into blood.—Acts 2: 20

|

In

educated circles people would soon be noting that all significant

advances in astronomy had been made since the Church lost its

grip on cosmology in the seventeenth century. Churchmen who

tried to hold the traditional line would find themselves distanced

ever further from educated opinion. Nevertheless, senior clergymen

continued to believe that angels were responsible for planetary

movement and other phenomena well into the nineteenth century

13. Some Christians

still do, but they are now a small minority. Mainstream Churches

have generally accommodated themselves to scientific discoveries,

although without ever admitting earlier errors explicitly. The

Vatican reviewed Galileo's case during the 1980s. After a ten-year

enquiry the Roman Church exonerated itself and justified its

earlier actions, an outcome that met with a degree of surprise

in the wider world14.

Cardinal Ratzinger speaking at La Sapienza University in Rome

(and quoting Paul Feyerabend) described the Church's position

as “reasonable and just”. This explains why, after

he became Pope Benedict XVI, professors and students alike complained

about his planned visit to the University in 2008, causing him

to call it off15. In

educated circles people would soon be noting that all significant

advances in astronomy had been made since the Church lost its

grip on cosmology in the seventeenth century. Churchmen who

tried to hold the traditional line would find themselves distanced

ever further from educated opinion. Nevertheless, senior clergymen

continued to believe that angels were responsible for planetary

movement and other phenomena well into the nineteenth century

13. Some Christians

still do, but they are now a small minority. Mainstream Churches

have generally accommodated themselves to scientific discoveries,

although without ever admitting earlier errors explicitly. The

Vatican reviewed Galileo's case during the 1980s. After a ten-year

enquiry the Roman Church exonerated itself and justified its

earlier actions, an outcome that met with a degree of surprise

in the wider world14.

Cardinal Ratzinger speaking at La Sapienza University in Rome

(and quoting Paul Feyerabend) described the Church's position

as “reasonable and just”. This explains why, after

he became Pope Benedict XVI, professors and students alike complained

about his planned visit to the University in 2008, causing him

to call it off15.

Bruno's

case has not yet been reconsidered, and most of the evidence

has apparently now mysteriously disappeared while in the custody

of the Vatican. There are, even today Christians who believe

that stars are really angels. Aparently they look like this

figure on the right, though it is not obvious why they might

need wings in a near vacuum. Bruno's

case has not yet been reconsidered, and most of the evidence

has apparently now mysteriously disappeared while in the custody

of the Vatican. There are, even today Christians who believe

that stars are really angels. Aparently they look like this

figure on the right, though it is not obvious why they might

need wings in a near vacuum.

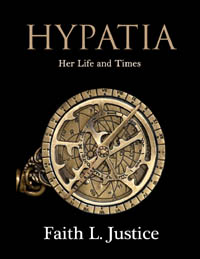

Hypatia was devoted to her magic, astrolabes, and instruments

of music .... She beguiled many people through her satanic

wiles.

Bishop John of Nikiu, 4 th century

One might imagine that pure mathematics could not pose too

much of a threat to Christianity. Not so. Mathematics was tantamount

to enquiring into God's mind, and such presumption could not

be permitted. Churchmen declared geometry to be the work of

the Devil, and accused mathematicians of being the authors of

all heresies. Ancient thinkers like Pythagoras were regarded

as having been dangerous magicians. In the third century the

Church Father wrote in his Refutation of All Heresies,

bracketed together "magical arts and Pythagorean numbers"

(Book VI) and includes mathematicians as one category among

"Diviners and Magicians" (Book IV).

Since Saint Paul himself, Christians had been burning books

on mathematics and science, regarding them as works of sorcery.

As Acts 19:19 puts it "Many of them also which used curious

arts brought their books together, and burned them before all

men: and they counted the price of them, and found it fifty

thousand pieces of silver." Any Christians who practiced

mathematics was likely to be accused of practicing sorcery.

Eusebius Bishop of Emesa ( ca. 300 - ca. 360), a mathematician

and astronomer, had to flee for his life because his flock imagined

him to be a servant of the Devil.

Pagan

professor were in even greater dangery. Hypatia,

a professor of mathematics and philosophy became head of the

Platonic School in Alexandria around the year 400. Her lectures

were seen as a major threat by Christians. She is thought to

have invented a new type of astrolabe, an astronomical instrument,

but Christians made no distinction between science and magic. Pagan

professor were in even greater dangery. Hypatia,

a professor of mathematics and philosophy became head of the

Platonic School in Alexandria around the year 400. Her lectures

were seen as a major threat by Christians. She is thought to

have invented a new type of astrolabe, an astronomical instrument,

but Christians made no distinction between science and magic.

In those days there appeared in Alexandria a female philosopher,

a pagan named Hypatia, and she was devoted at all times to

magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled

many people through Satanic wiles.16

She

revised her father's learned commentary on Ptolemy's Almagest

and wrote her own commentaries on the works of Apollonius and

Diophantus. In 415 she was seized by monks and other followers

of Cyril, the local bishop. They stripped her and dragged her

naked through the streets to a church. They cut off chunks of

her flesh with sharp sea-shells until she was dead, and then

burned what was left of her body. (read

John's account here >). Pagans were horrified, Christians

delighted. For them Cyril was a hero. They dubbed him Theophilus

or “Lover of God”. He is now Saint Cyril. Hypatia's

works are "lost" - almost certainly destroyed as books

of sorcery by zealous Christians. She

revised her father's learned commentary on Ptolemy's Almagest

and wrote her own commentaries on the works of Apollonius and

Diophantus. In 415 she was seized by monks and other followers

of Cyril, the local bishop. They stripped her and dragged her

naked through the streets to a church. They cut off chunks of

her flesh with sharp sea-shells until she was dead, and then

burned what was left of her body. (read

John's account here >). Pagans were horrified, Christians

delighted. For them Cyril was a hero. They dubbed him Theophilus

or “Lover of God”. He is now Saint Cyril. Hypatia's

works are "lost" - almost certainly destroyed as books

of sorcery by zealous Christians.

Another

great saint, St Augustine

of Hippo, often referred to as the Father of the Inquisition,

shared the opinion of his fellow saint and all right thinking

Christians: Another

great saint, St Augustine

of Hippo, often referred to as the Father of the Inquisition,

shared the opinion of his fellow saint and all right thinking

Christians:

The good Christian should beware of mathematicians and all

those who make empty prophecies. The danger already exists

that mathematicians have made a covenant with the Devil to

darken the spirit and confine man in the bonds of Hell17.

Because of such hostility, mathematics progressed only a little

beyond that of Euclid for many centuries. Indeed, the end of

the flowering of mathematics in the ancient world is usually

dated from the murder of Hypatia. How little progress was made

after her time is demonstrated by the continued use of Greek

textbooks. Euclid's Elements was still in common use

in Christian schools into the twentieth century, as were Hypatia's

astrolabes.

When

the cultivated Abbasid Caliph Haroun al-Rashid (he of the

One Thousand and One Nights) sent Charlemagne an astolabe

water clock in the early ninth century, Christians were horrified.

They did not recognise it as superior technology, merely as

a diabolical contraption designed to work some sort of Islamic

sorcery. When

the cultivated Abbasid Caliph Haroun al-Rashid (he of the

One Thousand and One Nights) sent Charlemagne an astolabe

water clock in the early ninth century, Christians were horrified.

They did not recognise it as superior technology, merely as

a diabolical contraption designed to work some sort of Islamic

sorcery.

The Church had its own use for mathematics. In the Middle Ages

almost all mathematical effort was directed towards calculating

the date of Easter, a matter that the Church believed to be

of the utmost importance. Complicated tables concerning so-called

golden numbers and the movements of imaginary moons, called

ecclesiastical moons, are still included in the Book of Common

Prayer for this purpose. Real mathematics was still a form of

diabolical magic, as was any use of Arabic numerals. In the

statutes of the "Arte del Cambio" in 1299 money changers

in Florence were forbidden the use of Arabic numerals, and were

obliged to use Roman ones'17a.

(It is only in the twenty first century that Christian theologians

have started to provide references to theological works using

arabic rather than roman numerals).

Michael Scot (1175 - c.1232) was a Scottish scholar. He knew

Latin, Greek, Arabic and Hebrew, but was most notable as a mathematician.

(The second version of Leonardo Fibonacci's famous book on Mathematics,

Liber Abaci, was dedicated to him). As a prominent mathematician

and proto-scientist he was believed by Christians to have been

a sorcerer or a magician, aided by demons. He supposedly feasted

on dishes brought fresh and hot brought by spirits from the

royal kitchens of distant countries. Other fanciful stories

were circulated. Scott once turned a coven of witches to stone

(they survive as a stone circle known as Long Meg and Her Daughters

near Penrith in Cumbria). He appears in Dante's Divine Comedy

(Inferno, canto 20.115-117) in the Eighth Circle of Hell reserved

for sorcerers, astrologers, and false prophets. Boccaccio represents

him similarly. He is represented as a magician with power over

demons in many other works, right up to Sir Walter Scott's The

Lay of the Last Minstrel.

When the concept of zero was introduced along with Arabic numerals

from the East, it was seen not as what it is, the most important

advance since ancient times but, in the words of William of

Malmsbury, as "dangerous Mohammedan magic". Zero was

literally satanic. As so often, the problem was that new learning

contradicted Aristotle. Aristotle had avoided ideas of zero

and infinity, and Christians thought they could not exist. To

them, the idea of zero looked to much like "nothing",

the empty void that God had done away with at the creation of

the world. Soon mathematicians and painters would extend their

heresy by discovering the concept of a vanishing point, and

the rules of perspective, advancing art to the level of classical

times. Even so, late medieval popes would lead an extended battle

against heretical zeros. Christian horror of the heretical concept

would resurface periodically as new discoveries were made, even

beyond the Middle ages: for example when a student of Galileo

discovered how to create a vacuum - a practical example of "nothingness"

in the real world - Christendom was riven by righteous horror

all over again.

|

Christians were reluctant to abandon

Roman numerals and adopt Arabic numbers because of the

heathen associations. Along with a terror of the heathen

zero, this ensured that mathematics could not advance

significantly within Christendom.

Even today the Christian calendar does not recognise a

year zero:

|

|

|

The

"Oxford Calculators" were a group of 14th-century

thinkers, almost all associated with Merton College, Oxford.

They took a logico-mathematical approach to philosophical problems.

When religious reformers cleaned up Oxford University they destroyed

an unknown number of mathematical and astronomical manuscripts

believing them to be conjuring books18.

It was almost certainly at this time that the great collection

of works of the Oxford Calculators disappeared. The

"Oxford Calculators" were a group of 14th-century

thinkers, almost all associated with Merton College, Oxford.

They took a logico-mathematical approach to philosophical problems.

When religious reformers cleaned up Oxford University they destroyed

an unknown number of mathematical and astronomical manuscripts

believing them to be conjuring books18.

It was almost certainly at this time that the great collection

of works of the Oxford Calculators disappeared.

In Tudor times mathematics was still a form of black magic,

and the terms conjure and calculate were used

as synonyms. Astrologers, conjurers and mathematicians were

regarded as being the same19.

In 1614 a Dominican preacher, Tommaso Caccini, could lampoon

Galileo and all mathematicians as magicians and enemies of the

faith.

John

Dee (1527 – 1609) was a consultant to Queen Elizabeth I.

One of the most learned men of his age, he had lectured on advanced

algebra at the University of Paris while still in his early

twenties. He was also a respected astronomer, as well as an

expert in navigation (having trained many of those who would

conduct England's voyages of discovery). Doctor Dee straddled

the worlds of science and magic just as they were separating

into distinct magisteria - he was for example still interested

in the language of angels. In 1555, he was arrested and charged

with "calculating". He supposedly cast horoscopes

of Queen Mary and Princess Elizabeth. The charges were expanded

to treason against Mary. Dee exonerated himself in the Star

Chamber, but was turned over to the (Catholic) Bishop Bonner

for religious examination. A series of similar accusations and

slanders would dog him throughout his life, though he was relatively

safe after the death of Bloody Mary in 1558. He is remembered

in Christian mythology as a necromancer rather than a mathematician. John

Dee (1527 – 1609) was a consultant to Queen Elizabeth I.

One of the most learned men of his age, he had lectured on advanced

algebra at the University of Paris while still in his early

twenties. He was also a respected astronomer, as well as an

expert in navigation (having trained many of those who would

conduct England's voyages of discovery). Doctor Dee straddled

the worlds of science and magic just as they were separating

into distinct magisteria - he was for example still interested

in the language of angels. In 1555, he was arrested and charged

with "calculating". He supposedly cast horoscopes

of Queen Mary and Princess Elizabeth. The charges were expanded

to treason against Mary. Dee exonerated himself in the Star

Chamber, but was turned over to the (Catholic) Bishop Bonner

for religious examination. A series of similar accusations and

slanders would dog him throughout his life, though he was relatively

safe after the death of Bloody Mary in 1558. He is remembered

in Christian mythology as a necromancer rather than a mathematician.

John Napier (1550 – 1617), the inventor of logarithms,

also attracted criticism. He was regarded as a magician, and

was imagined to have dabbled in alchemy and necromancy. Ironically,

he invented logarithms for the most Christian of reasons, to

help him calculate the End of the World from the information

in the Book of Revelation.

Even

in the eighteenth century scientists had to be wary of offending

churchmen. Newton's theory of fluxions, now generally called

differential calculus, the gateway to modern higher mathematics,

was perceived as a threat by leading churchmen. Bishop Berkeley

tried to refute Newton's ideas, seeing them as incompatible

with Christianity. Even then, in the eighteenth century, Berkeley

was complaining about Christians using "heathen zeros".

In 1734 he published a work entitled "The

Analyst; or, A Discourse Addressed to an Infidel Mathematician

..." directed against scientists like Edmund Halley.

In it he derides non-believing mathematicians with questions

such as "Whether the modern Analytics do not furnish a

strong argumentum ad hominem against the Philomathematical

Infidels of these Times". It is classic religious polemic,

similar to that produced by earlier bishops arguing against

Galileo, and to that of later bishops who would try to refute

Darwin. Even

in the eighteenth century scientists had to be wary of offending

churchmen. Newton's theory of fluxions, now generally called

differential calculus, the gateway to modern higher mathematics,

was perceived as a threat by leading churchmen. Bishop Berkeley

tried to refute Newton's ideas, seeing them as incompatible

with Christianity. Even then, in the eighteenth century, Berkeley

was complaining about Christians using "heathen zeros".

In 1734 he published a work entitled "The

Analyst; or, A Discourse Addressed to an Infidel Mathematician

..." directed against scientists like Edmund Halley.

In it he derides non-believing mathematicians with questions

such as "Whether the modern Analytics do not furnish a

strong argumentum ad hominem against the Philomathematical

Infidels of these Times". It is classic religious polemic,

similar to that produced by earlier bishops arguing against

Galileo, and to that of later bishops who would try to refute

Darwin.

The only reason Newton himself did not come under greater attack

was that he concealed his true beliefs about Christianity (he

did not accept that Christ was divine) and made a point of stating

that he hoped his work would be useful to Christian apologists.

His greatest work, the Principia, was deliberately

written in an abstract style so that only mathematicians would

understand the implications of it.

Christians

were also opposed to atomic theory, largely because the Greek

philosophers who had first proposed it had been atheists. These

philosophers had held that the world came into existence through

the natural interaction of atoms, and that life had developed

out of a primeval slime. Leucippus had first developed an atomic

theory, and it had been espoused by Democritus, Epicurus of

Samos and the Roman philosopher Lucretius. They held that there

is no purpose to the Universe and that everything is composed

of physically indivisible atoms, with empty space between them.

How else, they asked, could a knife cut an apple? If the apple

were solid matter such a thing would be impossible. Christians

were also opposed to atomic theory, largely because the Greek

philosophers who had first proposed it had been atheists. These

philosophers had held that the world came into existence through

the natural interaction of atoms, and that life had developed

out of a primeval slime. Leucippus had first developed an atomic

theory, and it had been espoused by Democritus, Epicurus of

Samos and the Roman philosopher Lucretius. They held that there

is no purpose to the Universe and that everything is composed

of physically indivisible atoms, with empty space between them.

How else, they asked, could a knife cut an apple? If the apple

were solid matter such a thing would be impossible.

Atoms were indestructible and were in perpetual motion, cannoning

off each other when they collided, or sometimes combining if

they interlocked. There were an enormous number of them, differing

in size, shape and heat, and governed by mechanical laws. When

men like Thomas Hobbes started to resurrect atomic theories

in the seventeenth century, Christians were alarmed by the revival

of this ancient horror. They were convinced that godlessness

was a necessary corollary of atomism20.

Perhaps they were right. The overwhelming majority of physicists

today are both atomists and atheists.

The religion that is afraid of science dishonours God and

commits suicide.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals

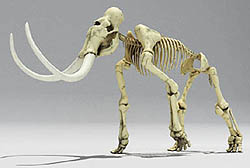

Animals

were an ever-increasing source of embarrassment to Christians.

For one thing it became difficult to believe that they had all

fitted into Noah's ark. As more and more species were discovered

it became more and more difficult to reconcile the facts. Where

was all the fodder stored, and what had the carnivores eaten

during the voyage? How were the tropical animals kept warm,

and the Arctic ones cold? How did Noah collect them all, and

how did they all get back home afterwards? Finally, why were

so many animals not mentioned in the Bible, God's infallible

and comprehensive encyclopaedia? Animals

were an ever-increasing source of embarrassment to Christians.

For one thing it became difficult to believe that they had all

fitted into Noah's ark. As more and more species were discovered

it became more and more difficult to reconcile the facts. Where

was all the fodder stored, and what had the carnivores eaten

during the voyage? How were the tropical animals kept warm,

and the Arctic ones cold? How did Noah collect them all, and

how did they all get back home afterwards? Finally, why were

so many animals not mentioned in the Bible, God's infallible

and comprehensive encyclopaedia?

Another problem was the question of why animals suffered, since

they had never sinned like Adam and Eve and incurred God's wrath.

One answer to this was that, despite appearances, they did not

suffer. They were mere soulless automatons, so it did not matter

what was done to them. This view has survived in the Roman Church

to this day. But if animals did not have souls, how could they

live at all? The answer to this was that they had a sort of

lesser soul, or spirit, or "vital force" much inferior

to a man's and even to a woman's , but indivisible just like

theirs21.

It was this spirit that animated them, just as souls animated

human beings. In the eighteenth century this theory came under

suspicion when it was discovered that movement persisted in

the hearts of animals after death. How was this movement possible

without an animating spirit? Again, muscle tissue, even when

removed from the body, would contract if pricked. But how could

tissue move without an animating spirit? Thinking people started

to suspect that life was not spiritual at all, but merely mechanical.

Such people were called materialists and were branded by the

Church as atheists.

Before Christians needed to counter evolutionary arguments

by claiming the need for divine creation of all animals, they

had been happy enough to adopt Aristotle's line that at least

some animals could be created spontaneously - without the agency

of gods or other animals. So for example rotting meat generated

maggots. Dirty laundry and wheat generated mice. These Aristotelian

ideas, once so central to Christian doctrine, had to be abandoned

in the nineteenth century. They had never been easy to reconcile

with the idea of animating spirits, and was now impossible to

reconcile to scientific discoveries, for example that maggots

do not appear in meat if flies are kept away.

The questions remained and indeed multiplied. If the human

personality was the outward manifestation of the human soul,

why was it affected by disease, or drugs, or food and drink?

For that matter why was it affected by age, or temperature,

or climate? Then in the 1740s Abraham Trembley discovered that

a freshwater polyp, or hydra, could regenerate itself when cut

into pieces. Did each piece have a spirit? If animal spirits

were divisible after all, why not human souls? For the time

being the question had to be left open, for inquisitive Christians

had still not yet succeeded in identifying the seat of the soul.

As soon as its physical location could be established, Christian

truth could be proved once and for all and the materialists

confounded. So far the search has been unsuccessful. The Churches

seem to have given up hope of identifying a biological soul,

and now deny that there is such a thing. Biologists long ago

switched to more productive areas of research.

Had I been present at the Creation, I would have given some

useful hints for the better ordering of the Universe. Attributed

to Alfonso "the Wise", king of Castile (1221-1284)

Leonardo da Vinci had suggested that Earth's past could be

explained by natural forces, but this suggestion was at odds

with the Christian view. God had made the world, and neither

it nor its inhabitants were mutable. Any theory that contradicted

this view was not to be countenanced. In the seventeenth century

the Bible was still the infallible source of all knowledge:

No one seeking to enquire into rocks or minerals, into Earth

history or the formation of Earth's configuration could afford

to ignore or deny the value of his primary source, the Bible22.

The immutability of Earth and its biology was to remain the

established view up to the nineteenth century. One factor that

constrained many pathways of thought was the chronology of Earth

and the Universe. The Jews had held that the world had been

created around 4000 BC (a belief that is still repeated at every

Rosh Hashanah and every Jewish wedding ceremony). Because of

an arithmetical error by a monk, it became accepted Church doctrine

that it had actually been created in 4004 BC. In the sixteenth

century Dr John Lightfoot, Vice-chancellor of Cambridge University

had even worked out the date and time: God started his creation

at 9 am on 23 rd October 4004 BC. Bishop Ussher's estimate in

the mid-seventeenth century differed by 3 hours. He placed the

time of creation at noon on the same day23.

A detailed chronology was worked out for the whole of the Bible,

with dates attributed to every event. Such chronologies were

accorded respect comparable to the biblical text itself. When

Thomas Paine pointed out the absurdities and contradictions

in the Bible in The Age of Reason, he laid considerable

stress on the absurdities of the received chronology. Both he

and his readers believed that an attack on these chronologies

was an attack on Christianity itself. Their common view was

that if the biblical chronologies were wrong, then Christianity

itself was discredited.

The

position that accepted biblical chronology could not be wrong

precluded any understanding of Earth sciences, or indeed any

possibility of initiating such sciences. That geological processes

took millions of years to shape Earth was unthinkable, as it

was unthinkable that evolution had been responsible for the

diversity of life on Earth. God did not make mistakes or change

his mind about his creation. Animal life was immutable. Mankind

had existed from the formation of Earth in 4004 BC, and so had

the various animal species. The rose red city of Petra was not

merely poetically half as old as time, but literally half as

old as time. Climate and geography were the same as they had

always been. God had created perfect animals, and allowed imperfect

ones like snakes, frogs and mice, to be made by demons or to

arise spontaneously from the process of putrefaction24. The

position that accepted biblical chronology could not be wrong

precluded any understanding of Earth sciences, or indeed any

possibility of initiating such sciences. That geological processes

took millions of years to shape Earth was unthinkable, as it

was unthinkable that evolution had been responsible for the

diversity of life on Earth. God did not make mistakes or change

his mind about his creation. Animal life was immutable. Mankind

had existed from the formation of Earth in 4004 BC, and so had